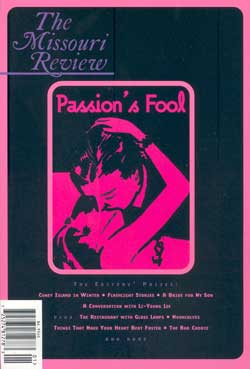

Interviews | March 01, 2000

An Interview with Li-Young Lee

Li-Young Lee ,Matthew Fluharty

Interview

- Li-Young Lee

- Matthew Fluharty Interviewer

An Interview with Li-Young Lee

Interviewer: We know from reading your work of your journey from Indonesia, through numerous countries and finally to Chicago. If someone asked you where you were from, what would you say?

Lee: That is a hard question. I think that all of my work is about destiny and interrogates that very question. I suppose I would say I don’t know. There is something in me that is absolutely American, absolutely assimilated, and there is something in me that is very resistant to assimilation. So is that Chinese? I have no idea.

Interviewer: How does this question of identity work its way into your poetry? How does it shape your view of poetry’s essential purpose?

Lee: I feel that the work of poetry is like making potato latkes. Every poem is like a potato latke, that’s all it is. On the other hand, it’s the most important thing a person can do. I suppose it’s because I believe poetry’s work is to uncover a genuine or authentic human identity, an identity even prior to childhood. It’s like the Zen question: What was your face before you were born? I think poetry tries to answer that, to come to terms with an identity that’s ancient and eternally fresh because it is so ancient. If you think about it, poetic speech is so dense because it accounts for the manifold quality of our being. There are many selves in me. As I am speaking to you now, I am speaking out of one self, the self that is in conversation. But there is a self that was dreaming last night. Poetry means one thing, but it means a hundred other things too, because we are as humans manifold in being. Poetry accounts for the many-ness of who we are, and I think that is why its voice is so dense.

Interviewer: Can you put a finger on some of the voices you are projecting into your work? Are they the voices of you, your family, your father?

Lee: I think the voice is a concerted voice, although we recognize that the richer a poem, the more manifold its voice. In my early poems, when I am talking about my father, he is the occasion for me to engage a certain kind of consciousness about him. There is something charged about his presence in my life, so that every time I emotionally encounter him this consciousness becomes present. Anymore I have given up distinguishing between my voice and my father’s. The question for me is: When I say “me,” what do I mean by “me”? Am I my mother, my father, my brother, my friends, my wife, my children, am I what I watched on TV? In the past scientists deluded themselves by saying there was an objective field of observation. It’s like the Taoists say: In the ten thousand directions, where can I look and not look by the light of the self? Physicists are now telling us that what they observe is themselves. The observer changes the field of observation, so what you observe is you. We are the lamp that we see by.

Interviewer: How do you deal with this when writing poetry? How do you channel this inner lamp?

Lee: I am listening for the voice all the time. It’s so simple to me that I am almost embarrassed because I don’t have any fancy theories. I just sit and wait to hear the voice. It is my voice and it isn’t my voice; it’s bigger than my own voice. Ultimately I think that is the subject. I guess I am saying the inner life is the only subject there ever was.

Interviewer: So does art fail in its task when it is based upon too much classification?

Lee: Art is the consciousness of all things simultaneously. That’s what makes art so dense and so mind opening. It is the final and first religious activity. This is what we mean by art being apocalyptic. Apocalypse means revelation. Art reveals who we really are. We are not Time magazine, CNN, we are not Laverne and Shirley. We are not just that, I should say. We are the Jackson Pollock action painting, Van Gogh’s Iris, we are Moby Dick’s whole theater of ocean. Every time you write a poem it’s apocalyptic. You’re revealing who you really are to yourself.

Interviewer: This brings to mind “Furious Versions,” a poem that seems to talk about this apocalypse. Especially in the later sections, the poem appears to be re-creating itself. Are we both the old poem and the humans re-creating the same atrocities under different names and different guises?

Lee: I am comfortable with both. Maxine Hong Kingston said, “I would love to live a life that is so big it could encompass contradiction and paradox.” This constitutes the idea of the all-self. We are both light and dark; we oppose ourselves. I had a feeling with that poem that we were revealing ourselves as these atrocious murderous beings, but of course, maybe that was when I was feeling really dark about things. A lot of the time I have infinite hope. What makes a person write a poem besides hope?

Interviewer: You also seem in that poem to be looking ahead to the new millennium.

Lee: Yes, I was. Maybe because of my Christian upbringing.

Interviewer: Do you feel there is going to be an apocalyptic moment?

Lee: No, not anymore. I suppose if we get caught up in a collective feeling of paranoia we will see who we are, but ultimately, no. Any time you dip your pen in the stream it’s apocalypse. What’s amazing to me is that apocalypse is happening right now. Every minute we talk it is occurring. The big mystery is revealing itself to us, but we’re so blind.

Interviewer: How did your family get to America?

Lee: I was very young when I came to America. I was born in 1957, and in 1962 I was six going on seven. I had already passed out of Malaysian. I spoke that fluently, and I lost it. I passed out of Japanese; we were there for eight months. My parents knew Japanese before that, so I was speaking Japanese pretty well, but I lost it. Then I spoke Cantonese when we were in Hong Kong, and I lost that. Finally, I spoke Mandarin and I learned English when I came here. I learned English when I was about eight, and I didn’t go to school till I was about eight. I went to kindergarten and I was the biggest kid in class; it was very embarrassing. When we came here we went to Seattle, then Maryland, New York and then Pennsylvania.

Interviewer: Do your children speak Mandarin?

Lee: They are learning Mandarin right now. They speak Italian and English. My mother only speaks Mandarin, so I speak Mandarin with her. I have an older brother we did not get out of China till twenty years ago, so he grew up there and was twenty-six when we got him out of there. He went through the Cultural Revolution and everything. He speaks only Mandarin. I speak Chinese with him, and I speak English with my sister and my two older brothers.

Interviewer: How important is it to you to show your children where you’ve come from?

Lee: I’ll be honest with you. In regards to my children, the emotional life between myself and my children has been very important to me, so I’ve cultivated that a lot. I’ve paid a lot of attention to that, probably to the exclusion of other things. I didn’t push Mandarin with them. I was losing it myself. I think the last time I was really fluent was when I was nine, but I began to realize that English was creeping into my language when I was talking with my mother. Now I am losing it so quickly that by the time I had kids I wanted the relationship between us to be very clear, very open and very true. I thought Mandarin was not my emotional language. Although when I went back to China I was dreaming in Mandarin and answering in Mandarin. By then my kids were already speaking Mandarin to their cousins. They were learning very quickly, and their inflections were perfect. So it must be down there somewhere.

Interviewer: How do you feel about your relationship to China now?

Lee: I don’t feel at home anywhere. I went back to China and I got stared at as much as I get stared at here. When I was growing up we would walk into a restaurant and everybody would stare. In Chicago it doesn’t happen so much because there are so many of us, and that’s why we moved here, but even my kids recognize that when we go back to Pennsylvania we walk into a restaurant and get stared at. My kids are half Caucasian and half Asian. I went to a small town in Alabama, and boy, it was scary. Everybody in the restaurant turned and stared at me and I thought I was going to get lynched. But then I went to China and I got stared at there also. People would walk up to me and say, “Where are you from?” I would say, “America,” and they would say, “I knew it. It’s the way you walk, the way you talk, the way you dress.” My cousins used to watch me wash my face in the morning and they would say, “You wash like an American. You move your hands, and we move our face.”

Interviewer: How many places did you and your family live before ending up in America?

Lee: We were in Tokyo, Singapore, Hong Kong, I was born in Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur. It sounds more exotic than it was. Mostly, we stayed in the house because we weren’t part of the culture. We weren’t on vacation, I wish we were, but it wasn’t like that. We spent a lot of time traveling, on ships, or in people’s homes—people who were housing refugees.

Interviewer: How did that experience affect the way you write and live now?

Lee: This is interesting because I recently realized something. My wife, who comes from a much different background, started renovating the house a couple years ago, and I didn’t recognize anything. I couldn’t get used to the idea that I owned anything; it seemed very strange to me. It felt wrong. I kept telling her, “I don’t recognize this life; I don’t like it. I don’t want to live this life.” We had a lot of difficulties. It wasn’t like I believed in not owning anything, like I was a socialist. It didn’t feel comfortable to me to know I owned a couch or a house. It was a new experience. We had these old broken windows when we first moved in here, and my wife had them replaced. I kept saying, “I don’t recognize these new windows. I recognize the old broken windows.” Because that’s the way we lived. My parents were always very poor, and we were always living in other people’s homes, like refugees. Catholic Relief Services had programs that would house people, and the Presbyterian Church had organizations all over the world where people would volunteer to house refugees. So we were always guests. I feel eternally that I am a guest and a stranger.

Interviewer: How did your family end up in western Pennsylvania?

Lee: We started in Seattle and we went to Maryland for a while and stayed with a family that took in refugee families. We stayed in New York City for a while in an old hotel that had been turned into a kind of church for homeless people. We cooked on a little hot plate and had a light bulb. We thought it was magical; it felt haunted to us. We worked the elevator, going up and down, one of those manual elevators. There used to be Sunday services downstairs; the weirdest people showed up, and they would serve them food afterward. We lived there for a while. It was very unglamorous. Then we ended up in western Pennsylvania. My father went to a theological seminary.

Interviewer: How did your vision of America change once you became acclimated here?

Lee: I always thought that an American is a white person, but it’s slowly coming to be not true. American has nothing to do with your skin color. It has something to do with your affiliation to democracy and freedom, so a black person could feel that way, a yellow person, a red person, you know. I think it has to do with my own re-envisioning what America is so I could feel comfortable here. But at the same time I guess I have to come to terms with feeling like a stranger all of the time. There isn’t a place on the planet where I am going to go and not feel like a stranger. This is home, though.

Interviewer: Is your poetry versed in America? Would you find yourself writing the same poems if you were in Tokyo or Jakarta?

Lee: No, I don’t think it is versed in America. Ultimately it has to do with this deeper allegiance, no longer an allegiance to my own skin color. It’s not attached to a place, and I’m not even sure it’s attached to the United States, because I feel great kinship with South American poets, and in fact sometimes I feel even more kinship to European poets than South American poets. I value feeling. I think a lot of times in North American poetry there is not a value of feeling. We are suspicious of feeling.

Interviewer: Does it bother you when journalists classify you as “Asian American”?

Lee: I look at that and tell myself it’s just more people thinking in classifications. That’s fine. I’m on my way somewhere else. I have good friends who don’t like this aspect of my thinking. They wish I would say I am fiercely Asian or fiercely American. I don’t, and I refuse to. I want to be a global poet. I think it is the only chance we have.

Interviewer: Do you feel people are expecting you to write a certain way? Like you should be writing about Asian American issues specifically?

Lee: After the fact. For instance, early on an Asian told me he was really offended by my book. I asked him why and he said he went through the table of contents and didn’t find any references to anything Asian. What did he want me to write? “A Night at Sun Wa,” or what? Maybe that’s why I try to stay out of those dialogues. It’s like “tar baby.” You throw a punch and your hand gets stuck. Next thing you know you are all rolled up in tar. I just stay away from it all. That will all blow away. It’s not interesting, ultimately.

Interviewer: You talk in The Winged Seed about how you were silent until age three and then went through bouts of silence until you were eight. I was thinking about that and also about some of your poems, like “I Ask My Mother to Sing” [from The City in Which I Love You]. In the poem you give us a beautiful scene of your mother and grandmother singing and starting to cry. Even after multiple readings, it is still ambiguous to me whether or not the poem concludes with their singing or their silence. To a lot of people the idea of silence and the idea of song are opposing forces, but they seem very related in your work.

Lee: You know, it’s almost like you can’t hear the silence without making a noise. You need to hit the gong to hear the silence afterward. It’s like Wallace Stevens saying, “I don’t know what I like more, the beauty of inflections or the beauty of innuendoes, the blackbird singing, or just after.” I think we need to make a particular kind of noise in order to hear silence. Not all noise invokes silence. Certain sounds put together invoke silence, and I think poetry tries to make those sounds.

Interviewer: Physically, can you see text as song and the space around the poem as silence?

Lee: Yes, very much so. The real test is when you read the poem, because you could lineate a poem so that it’s very deceptive, so that you look at it and you think it full of silence, but then you read it and it’s very noisy. There’s no silence; it’s like hysterical raving, which is, by the way, one of my qualms about Allen Ginsburg. I love him; I love the lawlessness. With a great sense of permission, he ushered in the self as the subject. We were no longer talking about Homer; we were talking about me. That’s what was great about him. But I would say his poems are strangely bereft of silence.

Interviewer: When you wrote The Winged Seed you used a word processor for the first time. How does the physical act of typing affect your work?

Lee: What happens is when I am writing a poem—and I am not kidding—when I write a poem, writing from left to right, my elbow will only go so far before it is uncomfortable. That for me is a line break. The arc of my elbow determines as much as my ear, and as much as my eye or the ache in my foot or the kink in my back. All of that figures into writing. It is a physical thing. So even the arc of my elbow will decide how far I will go with that line, but on a word processor … You know, originally I started that project as a poem. I wanted it to be lineated, but there were things that looked very prosaic, so I thought, “Okay, a prose poem.” I thought I would have to write it out longhand because I wanted to feel the act. My experience of time is different when I am writing longhand. Somehow the words cost more; it costs you more libido to write the words out along the whole page with your hand. And when I am typing on that thing there is no hard copy, unless you print, which bugged me. I was wondering, “So what am I typing on?” It’s just a screen. It’s like there is really no margin; the only margin is not real.

Interviewer: It’s a more cerebral act.

Lee: Yeah, it moves the body out, and I didn’t like that. I want the body in there; I want the body laboring. I want the poem to have some of the body’s labor in it, some of the fragrance. That was my problem with the typing part.

Interviewer: How did you deal with that problem?

Lee: Well, I wrote a lot of it longhand before I typed it on.

Interviewer: I’ve heard you say in other interviews that you wished you had another crack at The Winged Seed. Were you still writing the book after it was published?

Lee: I was. I think I gave up a year ago, and the book came out five years ago. After it came out I was still on it, so I kept writing. I have other versions, but they are so different.

Interviewer: Are they going to see the light of day?

Lee: I don’t know. Maybe someday when I know what I am dealing with. It’s so horrifying, so scary to me—the whole process of creating any art. I never know what I am dealing with. It’s like a weird monster that keeps changing.

Interviewer: You mention your elbow and the physical constraints of writing. Have you ever messed around with canvas? Just putting paper on a wall and seeing what happens, for instance if you were to map out a poem?

Lee: It’s funny that you should ask that. In my study I have two couches, and each of them is covered with a huge canvas that I wrote all over. I taped the canvas up on the wall and I wrote drafts of poems on them because I thought that’s what I needed to do. When I got done, I thought, “No, this didn’t work,” but I didn’t want to throw the canvas away, so I just threw it on the couch. It’s a couch cover with words written all over it. But I was talking with my brother, and I did want to do a project where I wrote on a canvas somehow.

Interviewer: In my research for this interview I came across some references to a fashion enterprise involving you and one of your brothers. What’s the story there?

Lee: My brother is a painter and he had a studio. One day we were sitting there and we might have been drinking beer or Coke or something—I think it may have been Pepsi—and he looked at the can, took a pair of shears and cut out a shape and put holes in it. He gave it to his wife and she wore it to work, and people thought it was beautiful. The next thing you know we were cutting out Coke cans and painting them, and he would mount them on a velvet sheet tacked to a piece of cardboard. There is a huge flea market here in Chicago. They play blues there and there are old black people playing blues and eating ribs. We drove a huge Chevy down there, popped the trunk and put up these black cardboard velvet things with these earrings and people would buy them. My wife started taking them around to stores. We moved from Coke cans to sheets of metal, copper and nickel, and we got a grinder. And then we got the wild idea to make them out of paper, so we made paper jewelry. Then Bloomingdales, Nordstrom, Bergdorf-Goodman, Saks, these huge companies were buying our stuff and we were working around the clock. I lived on that for a while. My wife was going store to store selling, and we started going to gift shows. Then we started moving into hats. Vogue did a big spread on that stuff, as well as Interview magazine and Cosmopolitan. We were doing okay, but it was really labor intensive. I was sleeping in the studio, and I would wake up and start working until I would lie down and go to sleep again. I remember at one point I had my baby son under the table, and I was rocking him with my foot while I was grinding copper earrings. We had a great time, but it was so labor intensive that it was obvious that we couldn’t produce as much as these stores wanted.

Interviewer: Is your brother still in this field?

Lee: No. What happened was that I have an older brother who paints as if his hand was possessed by God. He paints so fast that we hired him to come to Chicago, and he was painting this stuff, just cranking it out. When we folded, he took over. Now he is in New York doing it, and I am very proud to say that he is one of the few people who has survived. He has been doing it now for fifteen years, and we heard that the turnover in that field is very big, but they just buy his stuff. They’re crazy about it. I go to cities and I see a woman walking by with a big pin in her ear, and it’s his stuff.

Interviewer: In The Winged Seed, you seem to be getting toward a very Wordsworthian idea of an unmitigated language. Can there be success in that endeavor?

Lee: I think to an extent, whatever little successes we create we move ahead. We come closer to uncovering what is real. Scientists are telling us right now that everything is vibrations. This marble looks solid, but if we put it under an electron microscope it’s electrons, it’s vibrating. So everything is a vibration. Words are vibrations. The poem is a field of words, a field of vibrations. One of the ways I revise poems and read poems that I love is to hum the sentences. I am thinking of a Frost poem now, “back out of all of this now too much for us [Directive],” so many times I have looked at those sentences and just hummed them. I was shocked to find out later on he talks about where sometimes in a poem you tell its sound quality not by the words themselves but by the sentences, by the pitch and the frequency and the rhythm. I think that has something to do with humming. I think a lot of poems when you hum them you find out it is flat.

Interviewer: It would be harder to hum some poems, like “Blackberry Eating,” by Kinnell, because you would almost be choking in the act of humming.

Lee: Or try mumbling it. This is why I have a problem with discursive poetry. When it becomes too discursive there is no mumbling, there’s just the denotative meaning of the poem. There’s no dark river under it carrying the words. Sometimes I think words are like leaves on this stream, a darker stream of mumbling and humming that goes along. If it doesn’t have that, we are looking at only the denotative function of the words.

Interviewer: Let’s talk for a bit about—

Lee: Cooking? I love to cook. I love food. I see poetry as soul food. I cook every night.

Interviewer: How many people sit down with you for dinner?

Lee: Thirteen of us. It’s a very big family. Every night we cook together.

Interviewer: I’ve heard you all live in a flat together.

Lee: We live in an area of Chicago called Uptown. When we moved in it was like a battle zone. Drug dealers were walking their pit bulls out in the open. We lived beside a crack house, and there was prostitution. There were a lot of artistic types who moved in because of the cheap rent. But we’ve been there sixteen years now, and it has gotten a lot better, primarily because Vietnamese families have moved in, and they are very family oriented. There was once one little Chinese grocery store and one little Vietnamese grocery store, and now it’s called “Little Chinatown” or “Little Vietnam.” We moved into this falling down, uninhabitable house. But we pooled our resources and bought the thing. Right now my wife and two boys are sleeping in the same room because half the house is in renovation. It’s going to be nice when it’s done.

Interviewer: What function does your poetry serve within your family?

Lee: None. I’m the guy who buys the soy sauce. When they were little I was the guy who changed their diapers. Sometimes I am reading a poem to my mother and she will say, “You’re still at that?” To this late day she thinks it’s a hobby or an insanity I am going to give up. I do tell my children stories, but they are thirteen and fifteen and they don’t want to hear them as much as when they were little. I think it helps them somehow, gives them a feeling of an infinite background, that their background doesn’t end at the hospital they were born in. It helps them to look back at their father’s past and see an infinite horizon.

Interviewer: How did your family respond to the biographical nature of The Winged Seed?

Lee: They are very supportive of me. My mother can’t read English, so she didn’t read it, but I have aunts and uncles who have called and said, “Do you know he said this and this?” She thinks I am crazy, she really does. We were cooking the other day, and I was patting myself on the back. I said, “Now aren’t I a great son, don’t I love you?” I was kidding with her, and she said, “Of course you do. I’ve always known that. The only thing is, I beg of you—please, don’t go crazy on me.” Her concept of artists and poets is that they are all insane, which is wrong to me. The only possible sanity is art.

Interviewer: Did you have an idea early on that you wanted to be a poet?

Lee: No, I didn’t always know, but I wrote little things. I remember my brother and I caught a fish one day and I wrote a little poem, just when I was learning English. I wrote, “This is a marvelous fish, cook us a nice dish,” and we safety-pinned it to the fish. I thought that was a great poem. This is weird, but I feel like I am learning English right now; I still feel like I am a guest in the culture. Every time I pick up a book that is written in English, even if it is a translation, I am highly aware of the fact that I am reading a foreign language.

Interviewer: How was your college experience?

Lee: I went to the University of Pittsburgh and I was into biochemistry or organic chemistry, or something like that. I walked into a poetry class and the guy teaching was Ed Ochester. He was a great teacher, and I started reading his poems. I was just knocked out. He introduced me to contemporary American poetry. He showed me Gerald Stern and Phil Levine’s work. I think I had a double major in biochemistry and English. But I left college because I was having a miserable time. I was daydreaming half of the time and I had a lot of personal problems at home. My father was sick a lot, and I was married young. I felt like a stranger. I wasn’t a college student.

Interviewer: How were your poems at that age?

Lee: They were okay. A lot of the poems in Rose were written when I was an undergrad. From there I spent a year at the University of Arizona because Ed Ochester told me I should go to a writing program. He took me seriously, and if he hadn’t I don’t know what would have happened to me. I think I would have been in jail or something. But I went there and met some great people. I spent a year there and dropped out. I went to State University of New York at Brockport, and that was one of the most important years of my life. I dropped out and never finished, but they just gave me an honorary doctorate. There were great teachers and great people. They taught me how to read. I don’t think I even knew how to read English until I went to Brockport. All of the time I was one of those kids who just kind of got lost in the system. I never really learned how to read, but I kind of darted around that. I remember being in literature classes as an undergrad at Pitt and not understanding what I was reading. I didn’t understand the grammar and the vocabulary; you have to understand that all of our language at home was Chinese. My parents forbade us from speaking English. My mother would not answer me unless I answered her in Chinese.

Interviewer: Did the act of writing poetry impel you to reevaluate your relationship with this language?

Lee: Yes. It was a blessing to me because when I started really studying the language, it was poetry I was studying. You go right to the source, the uncut, the liqueur. To this day, when I am reading prose it’s like dishwater, but when I am reading poetry it’s like the real liqueur, the real thing.

Interviewer: How do you think that affects your poetry—if you are writing in a language that is foreign to you?

Lee: It feels great. It feels the same way as when you touch the body or face of a lover. It’s foreign. So it’s the same thing when I am using the language. I feel like I am touching the body of someone I love very much. The English language is like a lover, and the poem is like a body.

Interviewer: How do you feel about North American poetry?

Lee: I think that sometimes it’s afraid of schmaltz. You know, “schmaltz” literally means chicken fat. For me there is good schmaltz and bad schmaltz. You’re born, you die, people go to weddings, people go to war, they come back crippled, they come back heroes; it’s all schmaltz. Everybody’s walking around wounded; everybody’s falling in love with the wrong people. Life is schmaltz, and we sometimes forget that. There are poets like Yehuda Amichai, Neruda and Rilke who don’t forget that good schmaltz.

Interviewer: Do you think there is a preexisting American code of poetic conduct that limits schmaltz?

Lee: There was a group of poets selected to read for big businesses across the United States. I believe it was to promote creativity in the workplace. Many poets were on the list, and I got a call from my publisher, who told me I was not allowed to read. I asked why, and he said that they looked at my work and found it unfit for the workplace. My work is the safest in the world. There were people on that list whose work was angry, talked about social reform and even the overthrow of the government. My publisher thought the sensuality in my work made them nervous. It seems to me that maybe we are not as afraid of social reform as we are of feeling. A bunch of businesspeople wouldn’t have any problem listening to a poet ranting and raving about the government, because they feel that’s just a poet doing what he does. But if somebody went up there and read a poem and everybody wanted to break down and cry about their dead father, that’s no good. So maybe, ultimately, feeling is the dangerous thing.

Interviewer: Speaking of fathers, as you get older how would you define your father’s influence? Do you hear the voice of his rhetoric in your work?

Lee: I want to say this without too much disrespect. When he died he did me a great favor. He opened up the whole realm of death and the dead, and certainly I felt an even deeper mystery in the world. When he died he took part of me with him, and part of me lives there among the dead. Ultimately, the world of the dead is very present with us, and we’re not always aware of that. His death meant a lot to me. It allowed a lot of mystery. In a way I am always quarreling with him. He would find my views very heretical—the idea that the only God there is the God I project. I don’t find that heretical at all.

Interviewer: Have the dynamics of this quarrel changed as you’ve grown older?

Lee: I think so. I have been able to understand him more. At the same time, I would have to say it has gotten more intense, the tension between us. The love has grown too, because suddenly I realize he has all this tradition behind him. He has all of Taoism and Judeo-Christian religion behind him and I am just one person trying to write a poem, trying to prove all of that—all the God those people have projected—is me, just one little person.

Interviewer: In some respects, wasn’t your father accomplishing that projection as a minister? He was leading people in prayer. Isn’t the poem an act of prayer?

Lee: Yes, and maybe this is the old competition with the father and I’m not done with it. I feel that what I am saying in the poem is that the poem is the original religion. Art is the original religion. Paul Valéry said that religion is fossilized poetry. I believe that because if you look at religion, what is it but the worship of symbols? What is art but the creation of symbols? We as artists create them afresh, and thousands of people come along and pick up on one—crown of thorns, fish and loaves—and they worship that for thousands of years. But you know, Christ was a poet, and he came up with these symbols and people worshipped them.

Interviewer: How do you resolve the conflict between your impulses toward Eastern religion and Christianity? Or is it a conflict?

Lee: I see it as a tension. I see that Eastern religion has projected everything inside. Western religion projects everything … well, that’s not entirely true, but Judaism does project a historical God, so it’s outside. I like the tension; it sometimes wipes me out because I am trying to see both. Sometimes I experience deep bewilderment, like I don’t know if I am projecting from the inside out or the outside in. That whole wrestling is what it’s about for me. It’s not about bliss or peace, but resolving tension. I do experience a huge, supreme intelligence working out there at the same time I experience it in here. They both seem to speak truths.

Interviewer: Are you working as a poet toward a resolution, or to further define the tension between the two?

Lee: I am trying to live right at the seam and not go crazy. That’s what I am.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Apr 16 2024

A Conversation with Carl Phillips

A Conversation with Carl Phillips Carl Phillips is the author of sixteen books of poetry, most recently Then the War: And Selected Poems 2007-2020 (Carcanet, 2022), which won the 2023… read more

Features

Jan 08 2024

A Conversation with Andrew Leland

A Conversation with Andrew Leland Andrew Leland’s writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, McSweeney’s Quarterly, and The San Francisco Chronicle, among other outlets.… read more

Interviews

Jun 02 2021

A Conversation with Camille T. Dungy

A Conversation with Camille T. Dungy Jacob Griffin Hall Camille T. Dungy is a poet, essayist, professor, and editor based in Fort Collins, Colorado. She is the author of four… read more