Foreword | June 01, 2003

Foreword

Speer Morgan

The review in this issue of Sally Cline’s biography of Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald reminds me of one of my favorite minor works of literature. In 1945, five years after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s death, Edmund Wilson collected eight of Fitzgerald’s magazine essays, along with a scrapbook of formerly unpublished Fitzgerald material that included organized writer’s notes, poems, letters and even a few recipes. Wilson named the book The Crack-Up, after the title of one of the essays. It is the source of some of Fitzgerald’s best-remembered quotations, and it’s also one of the most engaging collections of a writer’s ephemera I’ve read—good reading in itself and fascinating in its demonstration of how hard Fitzgerald worked at his fiction. The title essay, along with two others, “Handle with Care” and “Pasting It Together,” had been published in Esquire in the mid-thirties to a flurry of condemnation. They are in fact classic personal essays in the tradition of Montaigne, written by an author looking back on life from a more seasoned viewpoint, trying to better understand the world, human nature and himself.

However, Fitzgerald’s key subjects were physical exhaustion, disillusionment and depression, which were not seemly topics for a middle-class writer to discuss. John Dos Passos called it an abuse of his talent to go “spilling” out his life like that. Hemingway, who was always game for putting down his former friends, called the essays shameful and cowardly. Fitzgerald’s editor at Scribner’s, Maxwell Perkins, thought that they were exercises in self-pity. Harold Ober, his agent, noticed that magazine editors became standoffish to his short stories, which, along with occasional jobs in Hollywood, had been the source of most of his income during his later career.

The title essay in The Crack-Up is less a raw confession than a personably written modern-day exemplum. The author begins by speculating about the roles of trauma and regret in mental self-injury. He gently suggests that what we imagine comes entirely from the outside may be as much the result of our own error: “Of course all life is a process of breaking down, but the blows that do the dramatic side of the work—the big sudden blows that come, or seem to come, from outside—the ones you remember and blame things on and, in moments of weakness, tell your friends about, don’t show their effect all at once. There is another sort of blow that comes from within—that you don’t feel until it’s too late to do anything about it, until you realize with finality that in some regard you will never be as good a man again. The first sort of breakage seems to happen quick—the second kind happens almost without your knowing it but is realized suddenly indeed.” Fitzgerald goes on to describe his own breakdown in some detail, beginning with his having “a strong sudden instinct that I must be alone. . . . I was an average mixer, but more than average in a tendency to identify myself, my ideas, my destiny, with those of all classes that I came in contact with. I was always saving or being saved—in a single morning I would go through the emotions ascribable to Wellington at Waterloo.”

The contemporary reader of The Crack-Up can hardly avoid having a mixed response to these essays, written long before our widespread discussions of addiction and psychological disorders such as depression. Fitzgerald may appear to avoid the real issues—that both he and his then institutionalized wife had been alcoholics who weren’t able to take care of themselves in the most basic ways. Yet by not being overly reductive or self-lacerating, Fitzgerald is able to speak more broadly and with a better sense of humor about his times. In “Echoes of The Jazz Age” he alludes to his generation’s lingering excesses: “Though the Jazz Age continued, it became less and less of an affair of youth. The sequel was like a children’s party taken over by the elders.” He describes his and Zelda’s aimless traveling, the vanity and bad attitudes that they reinforced in each other and their emotional extremes. In “Sleeping and Waking,” he writes briefly and entertainingly about his insomnia, which he dates to the night when he had a mock-heroic battle with a certain unkillable mosquito, an experience that made him “sleep conscious” for the first time in his life. In several of the autobiographical essays in the collection, he refers to the seduction and delusions of his early career. He quickly went from college to This Side of Paradise, a first novel so successful that it would have deceived the ego of anyone but a seasoned stoic—a person Fitzgerald definitely was not at twenty-four. Whether they deal directly with alcoholism or not, these essays were pioneering examples of the nonreligious confessional meditation. They were also surprisingly brave stuff for their time.

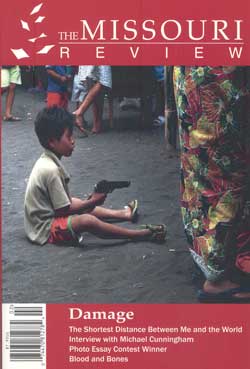

Like The Crack-Up, much in this issue of TMR concerns the damage that is done to people by themselves and by bad luck. The feature selection is Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s account of her 1939 journey by car to the remote regions of Afghanistan. Schwarzenbach was another glamorous figure of the 1920s and ’30s who died young due to her own recklessness. She was born into a wealthy Swiss family and raised in unusual circumstances—dressed and treated as a boy by her mother, who remained a strong influence throughout her life. She grew into a melancholy, restless person, talented at photography, fiction, and journalism. Klaus and Erika Mann, the son and daughter of Thomas Mann, introduced her to drugs, which were to be the bane of her life. Carson McCullers fell in love with the strikingly beautiful Swiss adventurer when she visited America and later dedicated Reflections in a Golden Eye to her. Despite Annemarie’s stormy personal life and struggle with opiates and alcohol, she traveled widely—in Afghanistan, the United States, the Belgian Congo, and North Africa—writing articles and several books. Her writing is haunting and compelling, and we appreciate translator Isabel Cole for making it available to American readers.

The problems of addiction, fortunately, are more openly aired today, as they are in two other selections from this issue. Michael Lundell’s stunning short story “Connect,” which reads like nonfiction, has both everything you didn’t know about heroin addiction and an unsettling, noir plot. Carolyn Michael’s essay “Renée,” about her daughter’s addiction, is both heartbreaking and as fascinating as any carefully constructed short story. A brief time before Renée started taking drugs and quickly graduated to heroin, she was a champion gymnast and superb student. Part of the fascination of Michael’s essay is her search for answers to the most natural questions a parent could ask: Why my daughter of all people? How did this happen—by what steps?

Tracy Crow’s nonfiction “Facelift” is somewhat lighter fare. Crow’s husband, who is twenty-some years older than she is, decided to have a facelift in an attempt to allay some of the damages of ageing. Her essay describes the procedure, its outcome and her own struggles now to resist the temptation to go under the knife.

Much of the damage and destruction in this issue comes to pairs. The two housemates in Ryan Harty’s story “Ongchoma” don’t talk much about their problems with booze, but they are without a doubt two tipplers who have found each other. They are also characters with all the unlikelihood of real life—he a gay Native American with an abusive boyfriend and she a disappointed academic with a mother who needs nursing after an operation. Peter Selgin’s “The Wolf House” is about another oddly real duo, twin brothers who have gone different ways. One has become a Unitarian minister now suffering a lethal case of disillusionment, while his twin is a factory worker with a sweeter disposition despite his failures. The narrator in Mark Kline’s powerful story “The Shortest Distance Between Me and the World” has been burned not by bad choices but bad luck. He is a warrior of good attitude and good faith, who must fight both circumstance and his caring but angry sister to survive.

In a thoughtful and revealing interview, author Michael Cunningham discusses the several incarnations that The Hours went through during the long period of its writing, until it finally reached a form that no one reasonably assumed would sell many copies. Cunningham is a great lover of books and excellent conversational company, as well as being a fine writer.

Issues of conflict, trauma, damage, and either decline or development have always been among literary fiction’s special provinces. When something goes wrong, how does it happen? Is it inevitable, or was there a moment when it could have been averted? Does it arise from a person’s background, their personality and emotions, their history of choices or some combination of these factors?

As young people, Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda were naïve romantics with high expectations. They’d both been doted on and spoiled by their parents. Scott, as a young adult, decided to learn how to write well, and with dismaying ease he did so. In her late twenties, Zelda fixed on the idea of becoming a ballet dancer and in fact did get surprisingly good at it. They both believed in the individual—the individual will, the individual voice and the individual’s ability to overcome anything. Yet they lived completely untenable lives, and in his finest work, Fitzgerald critiqued his own tendencies, as the love-bewitched protagonist of The Great Gatsby plunges into a life of illusion, ostentation and materialism trying to resurrect a relationship that never really was.

What happened to Gatsby in the end, though, did not happen to his author. He died young but he never gave in to illusion; he gained in humility; he never stopped writing; he died while writing The Last Tycoon, a book that—had there been time to finish it—could have been great. That same hopefulness is in one way or another apparent throughout the writing in this issue, as personal damage results, one way or another, in growth.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Jan 08 2024

Foreword: Family Affairs

Family Affairs During the nineteenth century, observers from both sides of the Atlantic admired the relative looseness of American families while also criticizing a lack of multigenerational connectivity and… read more

Features

Dec 19 2023

Foreword: The Curious Past

The Curious Past The past is such a curious creature, To look her in the face A transport may reward us, Or a disgrace. – Emily Dickinson Jonathan Rosen’s… read more

Features

Jul 27 2023

Foreword: The New Realism

The New Realism I sometimes wonder what the dominant trend in literature is going to be called. Names for artistic periods and movements are hardly definitive, but they are useful… read more