Curio Cabinet | July 21, 2015

Living Energy: the Abstract Expressionist Paintings of Michael West

Kris Somerville

Michael West, 1930. Photo: John Boris, Courtesy of Stuart Friedman

A work of art is born of the artist in a mysterious and secret way.

—Kandinsky

After her divorce from theater actor Randolph Nelson, to whom she’d been married a year, Corrine “Michael” West moved from Ohio to New York. She soon found an apartment in the Village and began studying painting at the Arts Students League. Her teacher, Hans Hoffman, was the founder of action painting. His theory of “push and pull” in an image to create form and texture appealed to her, as did his visceral technique of vigorous brush strokes across the canvas. He demanded his students’ total allegiance and in his classroom created a cult-like atmosphere. When another class member, Lorenzo Santillo, suggested that she meet his friend, Armenian painter Arshile Gorky, she at first refused, suspecting that he would be too much like their teacher.

On a cold March evening in 1935, however, West went with Santillo to a party at Gorky’s large studio on Union Square. She was uncomfortable; she had only been in New York a short time and worried that she smacked of provincialism. However, as she strolled down the hallway, looking at Gorky’s powerful pen-and-ink drawings, she was taken by his work. When she finally met Gorky, imposingly tall and shabbily dressed, she was smitten. She’d promised herself she’d never become a muse to the maestro, and now that threat had materialized; she sensed immediately that he would become one of her generation’s greatest painters. Gorky was equally charmed by West and her beauty. She used the name Mikael during this period, but Gorky insisted on calling her Corrine, liking the formal quality of it.

Their relationship quickly developed around their shared passion for painting. Since childhood, Corrine had been a devotee of the arts. As a young girl she’d studied piano, and attended both the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and Cincinnati Art Academy, where she became a skillful performer of Rachmaninoff. Also interested in acting, she was cast by the Cincinnati Actors Theater as Vivian in The Passing of the Third Floor Back. That was where she met and married Nelson, the male lead in the play. In their short year of marriage, she learned that her career was expected to take a back seat to being a wife.

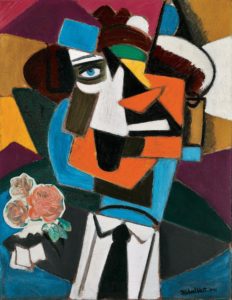

Poet in a Brown Hat, 1941, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Miriam L. Smith, Art Resource Group.

In New York, through Gorky, West gained entrée into the growing bohemian scene of the ’30s, and though she was unused to being around what she called a “group of intellectuals and intelligentsia” she soon felt that she belonged. They went to museums and galleries together and talked of their shared belief that painting was a mystical experience. They felt a similar connection to the spiritual and the poetic, and as artists they sought to direct this energy—this “scared feeling for life”—into their work. They saw the canvas as a battleground on which they were to “fight out their lives.”

“I think our excitement about art was rather unnatural. This tremendous love of art was where our identities collided,” West later recalled. Gorky thought he’d found the perfect mate and asked her to marry him. But despite their shared passions and philosophies, she felt as if Gorky understood her very little, and she declined. He asked her several more times, and she refused, confessing that her work would always come first. He promised that would not change, but his needs were already more than she could handle. Though she agonized over breaking up with him, she felt that he “needed a rich sophisticated person who would give him 2 children and help manage his career.”

Michael West, c. 1945. Photo: Richard Pousette-Dart. Courtesy of Stewart Friedman.

The New York art world of the ’30s and early ’40s was fueled by a search for what still needed to be done in painting—what the European modern masters hadn’t done already—and the city was becoming the center of that exploration. Abstract Expressionism, which was developing along with the city’s explosive spirit, was less cerebral and inspired less by outside influences than by an inner compulsion. Painting became more an expression of what inhabited the jungle of the artist’s mind than an art based on objective standards.

Michael West, 1947. Photo: Francis Lee. Courtesy of Stuart Friedman.

What was eventually called the New York School was decidedly male dominated, with its leaders Hans Hoffman, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky. West was one of the few females artists, along with Lenore (Lee) Krasner and Grace (George) Hartigan who were active in the movement. They believed that style dominated subject matter; in fact, style was the subject matter. An artist was to strive to think and feel what the painting iswas not what it showed. Spontaneous gesture should evoke a very immediate response, and the use of color should spark the imagination.

West didn’t appreciate being in the shadow of men, even if she admired them greatly. She was fiercely independent and eager for recognition as a professional artist. In the ’40s, her unique style of Abstract Expressionism began to find an audience intrigued by its wild, stark, brutal quality and its unruly tussle of color and line. Inspired by French philosopher Henri Bergson’s concept of living energy, or creative impulse, she took a passionate, instinctive approach to painting, filling her canvases with vibrancy and raw force. She adopted Bergson’s idea that a new world is waiting to be discovered by trusting in the creativity of instinct. Intuition, not analysis, reveals the world to artists.

Red Composition, 1967, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Miriam L. Smith, Art Resource Group

In 1948 Michael married Francis Lee, an experimental filmmaker who during World War II had joined the infantry and was assigned as a combat cameraman. He shot some 500,000 feet of film that thirty years later was fashioned into a 20-minute documentary. The couple worked diligently by day in their artistic media and in the evening frequented the Cedar Tavern, a bar on 24 University Place where Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and other Abstract Expressionists hung out for the cheap liquor and protection from tourists and middle-class squares.

While Abstract Expressionism took off and for decades was the “house style,” its popularity didn’t do enough to boost West’s career. She received less press and fewer exhibitions than her male peers, though she eventually showed her work in Manhattan’s prestigious Stable Gallery in 1953 alongside de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Philip Guston. In 1957 she had a solo show at the Uptown Gallery in New York City, and another in 1958 at the Domino Gallery in Georgetown, Washington, DC.

Moments, 1970, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Miriam L. Smith, Art Resource Group

Though a jilted lover, Gorky remained a fan of West’s work, saying that “it is like no other American painter.” His support always meant a great deal to her and perhaps encouraged her to continue producing several hundred canvases long after he died in 1948. She loved the process that she characterized as working in the dark and feeling her way forward. Each line or color, added and then subtracted, was an ongoing experiment in her quest to tap into the uncontrollable forces of motion around her. At the end of her career, she hoped that her art communicated to the viewer a vision of life’s wonders and mysteries.

KS

Thank to Miriam L. Smith of Art Resource Group and Michael West’s executor, Stuart Friedman, for their support and assistance.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Curio Cabinet

Jan 04 2024

Eva Tanguay and the Art of Self-Promotion

Eva Tanguay and the Art of Self-promotion “It has all been done before, but not the way I do it.” –Eva Tanguay In February 1909, just before her Sunday… read more

Curio Cabinet

Dec 18 2023

Maud Allan and the Price of Fame

Maud Allan and the Price of Fame Kristine Somerville When Alfred Butt booked Maud Allan for a two-week engagement at the Palace Theatre in London in 1908, he added women-only… read more

Curio Cabinet

Jul 27 2023

Curio Cabinet: Selling Amelia Earhart

Selling Amelia Earhart In 1928, a year after Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic, New York publisher George Putnam hoped to sponsor the first woman to make a similar… read more