Foreword | January 01, 1984

Preface

Jo Sapp ,Speer Morgan

Some time ago we received a letter from Philip K. Dick, one of the most highly regarded contemporary authors of fantasy and science fiction. In it, Mr. Dick claimed to have been profoundly influenced by a story in the Missouri Review, the reading of which, he said, put him back on the track of a kind of writing that he felt he had abandoned in the pursuit of high remuneration.

Afraid that we were proving to be a bad influence on Mr. Dick but proud of his kind words, we mentioned it whenever the opportunity presented itself. To our surprise, people well versed in science fiction seemed to think that our having received a letter from Philip K. Dick, no matter its subject, was a fine thing—indeed, an amazing thing. We had been visited, it seemed, by an extraordinary notice.

It was our first lesson in the milieu of science fiction—a world of enthusiasts and devotees, where good writers are regarded as kings and queens, and very good ones as demigods. Yet in all of its forums, the field is characterized by an indefatigably democratic spirit. Writing by newcomers is seriously read and reviewed; there are frequent conventions, meetings, and colloquia. On any given weekend, the chance is high that there is a “major” SF convention going on somewhere.

Following our newfound interest, we discovered that it is probably the most difficult genre to define or even identify. In telephone conversations and interviews we did discover how not to identify it. Never call it “sci fi.” People who know, even mild persons whose acquaintance you have just made, will immediately put you in your place. “SF” is acceptable, but never “sci fi.” Some writers decline the term altogether; they deal, they say, in “alternative” or “speculative” or “fantastical” fiction. We have left the task of describing the modes and boundaries of the genre to Algis Budrys, an acknowledged expert.

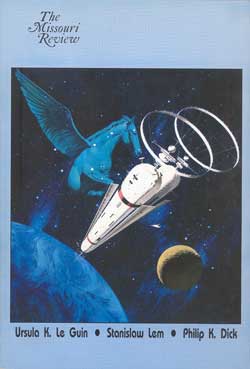

The stories assembled here can best be characterized by their diversity. In practice, the dividing line between “serious” fiction and science fiction is a ghostly and shifting entity. Unlike most of the other genres, science fiction is flexible in technique, subject matter, tone, and level of experimentation. Some subcategories tend to be formulaic, notably the horror and adventure stories aimed at teenagers (the kind of writing that Philip K. Dick had grown tired of), but if indeed SF is a “genre” it is a multifarious one. The three interviews in this issue are a further demonstration of its diversity. Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin, and the Polish author Stanislaw Lem are all writers who make the materials of SF their own.

Among the essays, we have included an article by Louis Gallo on modem physics in an effort to balance the fiction with a little science—an effort whose success our readers may judge for themselves.

Philip K. Dick died while we were assembling these materials. To him, and his fine work, we dedicate the issue.

Speer Morgan

Jo Sapp

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Jan 08 2024

Foreword: Family Affairs

Family Affairs During the nineteenth century, observers from both sides of the Atlantic admired the relative looseness of American families while also criticizing a lack of multigenerational connectivity and… read more

Features

Dec 19 2023

Foreword: The Curious Past

The Curious Past The past is such a curious creature, To look her in the face A transport may reward us, Or a disgrace. – Emily Dickinson Jonathan Rosen’s… read more

Features

Jul 27 2023

Foreword: The New Realism

The New Realism I sometimes wonder what the dominant trend in literature is going to be called. Names for artistic periods and movements are hardly definitive, but they are useful… read more