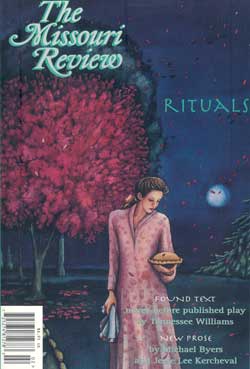

Fiction | September 01, 1997

Sentinel

Nick Hershenow

Across the river the chef de poste turns up his boom box, and frantic and repetitive music crosses the water. A noise to shatter the serenity of the tropical evening, except we’re already plenty agitated, all of us: the insects buzzing and shrieking and clicking in the strip of forest by the river, the bats scuffling and snarling in our attic, the mourners chanting to drumbeats in a clearing in the camp. And the Consultant standing on his porch looking out on the night, rocking and swaying to that radio music.

The first time I heard it I thought this music might eventually make me insane, but I have since learned how to channel it, along with a lot of other noxious stimuli, into passive background regions of my subconscious. This is not easy, since music here is always played at the highest possible volume, emphasizing distortion and accelerating speaker damage. But I watch the chef de poste and try to listen to music like he does: to take it in with my entire body, and not filter it through any analytical brain tissue. When I do this right the music longer bothers me, and sometimes I even start dancing myself. People laugh and stare, but this inhibits me less than I’d expect—they laugh and stare anyway, no matter what I do. I may as well make a spectacle of myself by dancing, since I achieve the same effect by reading a book or tying my shoes.

Placide didn’t laugh the first time he saw me dance. He came close to me and watched, a look of wonder on his face. I smiled, but he didn’t smile back.

“I’ve seen this before,” he said, when the music ended.

“What?”

“I saw it often in the capital, when the whites danced. Le Jerk. It must be a very difficult dance, monsieur.”

He spoke gravely, and did not respond to my laughter. But I think he must have been kidding me. It’s hard to tell with Placide. He comes up with outrageous statements, devotes his life to an absurd duty, and yet comports himself always with serious and measured dignity. Night watchmen are an uncanny breed, they say, and tiny Placide, who spends most of his waking hours padding around our compound with his bow and arrow at his side, peering into the nighttime shadows, is perhaps even more mysterious than most.

He’s out there somewhere in the darkness now, patrolling the compound. Two or three times I’ve seen his flashlight come on for a second, but otherwise I never know where he is; he walks silently, on bare feet that are cushioned with callouses like the paws of a cat. He’s small and dark and quick, with an affinity for shadows, and is capable of remaining very still for a long time. On a moonless night like this I won’t see him, until he appears to warm himself by his fire.

A wind comes up, fanning the coals in his brazier down by the cook shed, sending a few sparks skittering across the garden and carrying the smell of the fire up to the porch. It is a strange, sweet smell, the burning charcoal of a tropical wood, a smell unknown in higher latitudes. The glow of the fire illuminates the corrugated tin siding at the corner of the cook shed, and in the faint reflected light I can make out a couple of scraggly goat-eaten tomato plants in my vegetable garden. But away from that glow the night is completely dark, and its sounds—drums and thunder, insects, boom box music—come to me across invisible spaces.

Like me, Placide stands in the shadows and looks out on those spaces. The difference is he can see something. I’m sure he can see me jittering up here on the porch, dancing my inscrutable Jerk. I stop myself. Placide doesn’t care, or at least his sense of professionalism prevents him from passing judgment; but I guess I’m not yet entirely free of self-consciousness. And Placide’s dignity inspires me. I’d like to learn to move through the night with a hint of his grace and stealth, and these convulsive responses to music are not compatible with that goal.

So I still my quivering muscles, though the radio music is really wild now, accelerating as if to a climax. But in fact these hysterical and redundant riffs are not going to stop anytime soon. These songs go on and on, and they’re never formally concluded. After countless repetitions each song is finally just chopped off, which makes me wonder what actually happened in the studio or bar where the song was recorded—beyond the patience of the sound technician had there at last been a conclusive ending, or had the musicians played on and on until they collapsed, one by one, in exhaustion and madness?

There is a sudden commotion over my head in the attic, some pushing, and the indignant squeal of a bat. I hear flapping and snarling, and then silence again as the bats drift back into a resentful sleep. Out of the darkness at the foot of the porch steps comes Placide’s quiet voice, startling me as always. How does he come so close, so silently?

“Monsieur Consultant.”

“Placide. What’s going on?”

“Nothing. Peaceful. Will Madame Kate be home soon?”

“Maybe. She went to the funeral dance with some other women. I imagine it will be over soon.”

“The women will dance all night, monsieur. Our child died today. She was sick, and then she died.”

“Yes. It’s sad. I don’t think I knew that little girl.”

“You knew her, monsieur. You shook her hand, many times.”

There is an accusatory tone underlying Placide’s flat statement, as if he is suggesting that the repeated touch of my hand was somehow linked to the child’s death. Or that I should have somehow intervened to prevent her death. Or that I wrong the dead by not remembering her. But how am I supposed to remember her? There are a thousand children up there, all of them grimy and undernourished, feverish and afflicted, thrusting their filthy hands at us every time Kate and I venture into the camp.

“I’ve got crickets to burn,” says Placide.

“Good.” My response is automatic. I have no idea what he means. Probably he didn’t say he had crickets to burn at all. My mastery of Kituba is still shaky, creating plenty of opportunity for miscommunication. On the other hand people do some remarkable things. Possibly cricket burning has something to do with the performance of Placide’s duties, which I understand only vaguely.

The little girl, five years old, had come into the dispensary a couple of days earlier. She had a fever and some sores on her leg. The nurse treated her, and two days later she was dead.

“Why did that little girl die, Placide?” There is no answer. Placide is gone, having vanished as silently as he appeared. It is a wonderful thing to see, or rather to not see: a nocturnal man, blending so artfully with the night. But his talent seems wasted here, watching our little house night after uneventful night. He should have been something else—a hunter, a guerrilla warrior, a spy, a thief.

The fire flares a little and a shower of sparks goes up, though there is no wind. Placide is hunkered down, poking at his coals with a stick. In the glow I can see his face. He stirs the coals, and stares into the fire. I’m the silent one now, the invisible watcher, trying to comprehend a waking life centered on a small fire in an iron pan, with a great darkness over half the world.

That is Placide by night. By day he doesn’t seem like much, a small polite man, a little shabby. But people are afraid of him. Maybe they see a man who has spent too much of his life in the world of spirits. Maybe they are afraid of what he has seen peering into the shadows every night, or what he has imagined.

At first Kate and I were merely amused by Placide. We thought he was cute, I suppose because he is short, because he has a pug nose and an implacable deadpan and he wears a watch cap, and tattered overcoat in the tropical night. Because he has a hoarse piping voice and speaks a light and syncopated language that sounds charming to us, accustomed as we are to the guttural rumbling tones of English.

Such attributes create a facade of cuteness, a sentimental illusion obscuring an uncute reality. It took only a few sleepless nights inside our claustrophobic house, with Placide skulking around the compound, to shatter that illusion. Now I don’t know which is more unnerving: to see him huddled in his overcoat by the fire, casting a flickering and deceptively large shadow against the cook shed; or to not see him yet know he is there, peering from the night at my pale and nervous face. What is he doing out there all night? What’s the point of it? How does he even keep himself awake all night, with no danger to ward off and scarcely a passerby to challenge?

Next to his small fire he has a cement block to sit on, and inside the cook shed he keeps a pile of old cardboard, which on cool nights he sometimes drags out beside the fire and crawls beneath for warmth. But he doesn’t fall asleep, or if he does it’s a vigilant sleep, because he instantly emerges, bow and arrow in hand, at the slightest sound.

Now he sits on his cement block, hunched by the fire with his back to me. I might almost imagine that he’s dozing, but when I step off the porch he is on his feet and looking towards me. He waits calmly as I approach. But how does he know for certain that it’s me? Can he really see through this heavy darkness, or distinguish the sound of my footsteps from any others?

“You’re not sleeping, monsieur?”

“Not yet. What time is it?”

He pulls back his sleeve and stares at the glowing numerals on his digital watch. Crunching something in his mouth, he shows me the watch. Twelve seventeen.

“What are you eating, Placide?”

“Cricket.” He holds up half the charred body of a cricket. Of course. That’s what he said he was going to do—roast, not burn, crickets. As usual, my translation was flawed.

“Would you like one, monsieur?” He hands me a cricket, still warm from the coals. He pops the other half of his cricket into his mouth, and I slip mine into my shirt pocket. I have yet to eat a cricket, though Placide, who stalks them by night and tosses them live onto his coals to roast, sometimes gives them to me, ever since he got the idea from one of our garbled conversations that I consider them a great delicacy.

“Madame Kate is out late,” he comments between crunches.

She is. The distant thunder rumbles and the drumbeats roll on, as monotonous and repetitive as the clicking and buzzing of insects. But the chef de poste’s radio, I realize suddenly, is silent. How long has it been off, and how did it go off without my noticing it? How can that intrusive noise be assimilated so easily into the soundscape of the night? Insects and water, thunder and drums, the occasional soft calling of women’s voices. And the chef’s radio going silent, as unremarked as a night breeze dying out in the leaves of the palms.

“I’m going for a walk.”

Placide stares at me, uncomprehending. Maybe I used the wrong word. Maybe there is no way to express the idea of ‘going for a walk’ in his language. It’s too frivolous a concept, I think, a pointless squandering of limited energy, especially at this hour. The spontaneity, the carelessness, the pure nuttiness of going for a walk at night—Placide can hardly respond to this.

“I’ll check on Kate,” I add. Now Placide nods gravely, and squats in the glow of his coals to decapitate another cricket with his careful little fingers.

I go out the gate with my flashlight in hand, but switched off. Lately I’ve been purposely walking around at night without using a flashlight. This started on moonlit nights, when I realized the light was superfluous at best, but recently I’ve even tried it on dark nights like this. What I’ve been thinking is that the flashlight doesn’t illuminate the night so much as create an artificial day. The beam lights up a cone of space but changes everything that occupies that space. I suspect some night objects of becoming invisible when the beam hits them and outside the beam the night becomes entirely opaque.

Without a flashlight I have begun to penetrate the actual night. I have found that my eyes physically adjust to darkness, that my brain can learn to decipher night shapes. And I’m learning to use other senses as well, and to move with more confidence even when I can’t see, which is not necessarily a good idea. Scrambling confidently up the path, I lose my footing on the wet clay and slide heavily into the narrow ditch that runs above our house, soaking a boot and a leg in muddy water, and slightly twisting my ankle.

“Monsieur!” Placide is already at the gate, heading up the path.

“It’s okay. I just slipped into the water a little.”

“You should turn on your flashlight, monsieur.”

“I don’t like my flashlight. It keeps me from seeing the night.”

“Oui, monsieur. But it helps you to see the ditch.”

This advice is irritating, coming as it does from Placide, who never turns on his flashlight to see the ditch. But I say nothing; I just flick on my flashlight and follow the beam into the camp.

Away from the river the night is hotter, and there is no breeze at all. I hear distant thunder, and see the flicker of lightning through the trees, still too far away to illuminate the night. But entering the camp I risk turning off the flashlight again, and become aware of the vast number of stars above me: so many sources of light in the sky, and the land is so dark.

In a circle on the edge of a fire the women dance, swaying, their arms around each other’s hips. The sweat glistens on their arms and faces. Their eyes are closed, or unfocused. They sing, a murmured chant in the language of the village, incomprehensible to me. They lean on each other as they dance, and the circle ripples but never tears. No one stumbles, though they must have been dancing for hours.

Only one man is drumming, and the drums and the chanting are the only music. The drummer is in the shadows on the edge of the circle of dim light; his eyes shimmer, his sweat glints, the palms of his hands flash with his intricate beat. A few men stand near him, watching the dancers and talking quietly. Here and there is another small cluster of people, and others are lying on mats in the clearing, or in the doorways of huts. The fire and a few candles and palm oil lamps give off a dim flickering light. People duck into a hut, there is conversation, even laughter, and several men greet me as I approach the outskirts of the gathering, though I don’t know how they see me in the darkness. I stand stiffly, my ankle throbbing a little, my pant leg wet and clammy.

“Monsieur Consultant.”

It’s the chef de poste’s secretary, Mukatalika or something like that, I can never remember his exact name.

“Secretary.” This is a neat trick I have recently learned. A title can be used in place of a name. People are flattered, and it makes me feel colloquial, as though I’ve lived here a long while.

“Are you looking for your wife, monsieur?”

“Yes. I don’t see her here.”

“She was here earlier. She danced with the women.”

“I wish I’d seen that.”

“She dances well, Consultant! Different than you. Much better than you.”

“Really? That’s interesting, Secretary. Do you know where she is now?”

“She left a while ago, with her friend the nurse. I’ll ask where they went.”

I stay on the outskirts while the secretary makes his inquiries. I want to avoid the commotion my presence always creates, to observe for a moment but not intrude. I’ve never been to a child’s funeral before, and I didn’t really give this one any thought before I showed up. Of course I was listening to the drumbeats and the women’s voices, but these were just sounds of the night, like insects and thunder and radio music, part of what keeps me out on my porch in the night.

But now I see sweat-streaked, tear-streaked faces in the orange light, people wrapped in their pagnes lying on the hard ground, and the circle of women swaying deeply, holding each other up. The dance is simple and monotonous, yet hard to follow. Each individual woman seems to be going down, but the circle remains erect. They yield to pull of gravity without falling, and somehow their dance helps everyone bear the sorrow of putting a small body into the ground.

I ask a man what the child died of. He shrugs. A change in atmosphere, another man says. The rains have been hard, and she was not a strong girl. The men nod. The girl’s father had an argument with her uncle, one says. The uncle hired a fetisher, and the fetisher killed her. The men nod again.

The secretary is at my side again. I decline his offer to take me to the nurse’s house at the far end of the camp, where Kate may have gone.

“It’s okay. She’ll probably be back here soon, or at home.”

The secretary rocks and sways too, leaning toward me; I smell the sour palm wine on his breath. We stand together for a couple of minutes, swaying, but we keep bumping shoulders and knocking each other off balance. Is the secretary drunk, or am I having my usual problems with the rhythm? But I feel this drum music, it’s coming through to my bones, I even feel the grief it conveys, in some way that is not entirely abstract. I want to sway like the women, smelling the woodsmoke, with sweat on my neck and the dim orange light of fire and lamps falling on my closed eyelids. But again we bump shoulders and though my eyes are closed I can sense the secretary looking at me. I pretend I was nudging him.

“I’m going home now, Secretary. Goodnight.”

“Goodnight, Consultant.” The secretary stops swaying to shake hand, and I turn away into the darkness and follow the tunneling beam of my flashlight home.

“I see you’ve got your flashlight on, monsieur. Very intelligent.”

It’s impossible to tell how much irony, if any, is implied in Placide’s compliment. In some ways Placide must think I’m pretty dumb, for example in my inability to handle a flashlight, but in other ways I know that he thinks I’m extremely intelligent, for example in my ability to build a jet airplane. He said as much to me once, that jet airplanes were proof of how much smarter I was than him or any of his countrymen.

“What are you talking about, Placide? I don’t have any idea how those things work.”

“But you build it, monsieur. It flies.”

“Look, I didn’t build it. I couldn’t build a plane any more than you could.”

I saw that he didn’t believe me and tried to explain with an analogy. “It’s like in the village. Somebody knows the best wood for making a boat, the best way to make it. Nobody else has this knowledge—you just go to him if you want a boat made. Or maybe some old woman knows the plants in the forest that cure a fever. Other people have no idea, so they go to her when they’re sick. It’s the same with us and airplanes—a few people understand how they work, how to build them. If the rest of us want an airplane built, we go to them.”

Placide shook his head. “In the camp we eat the plants the old woman gives us, but the fevers keep killing us. As for you, your airplanes fly.”

“I don’t have anything to do with those planes, Placide. ”

“You belong to the knowledge, monsieur.” How could such a high popping voice sound so somber? And why do conversations like this always leave me feeling naive and foolish, while Placide turns away with his dignity intact?

But the question for Placide is how do you deal with somebody who knows how to make airplanes but doesn’t have the sense to turn on a flashlight in the dark. You might speak ironically to him and you might not. You might find him ridiculous and you might find him awe-inspiring. So I never know how Placide is taking me, how straight he’s playing me.

Now he huddles by his fire and gives me a sidelong look. I can’t quite make out what he’s asking me. Did I or do I like something? The funeral dance, maybe? My walk? His uncharacteristic grin and enthusiasm indicate that he expects me to say yes. Okay, I liked it, I say politely, and his grin broadens, his head bobs.

“It was good, Placide.” This is a safe elaboration that should not betray my incomprehension.

“Try again!”

Try what again? A different adjective, maybe? But I know so few. “Beautiful, Placide. It was beautiful.”

“Oh beautiful, monsieur, yes!” Placide is actually laughing. “Tasty, eh?”

I nod and break away, heading for the porch. Tasty? It must not have been the dance or my walk he was asking about. I sit in my rocker trying to figure out what Placide and I have just said to each other. Again we have bumbled our way through a conversation that began with an unintelligible premise. But we both know it wouldn’t do any good to stop and try to clarify what we are saying, since with Placide and me clarification is just another means for further muddling the sense of things. Anyway, clarity is only one of many possible attributes of conversation. We also value mystery, allusion, tone, momentum, and the camaraderie we are building—all things which can’t withstand the interruptions required by a dogmatic insistence that we understand what we are talking about.

And in fact Placide and I, with our brief and inconclusive exchanges throughout the long nights, have forged a kind of bond, transcending our difficulties with the language and the less-than-solid ground on which we encounter one another: he the Night Watchman who guards against nonexistent terrors; I the Consultant who transfers the intangible knowledge. Together we smell the smoke of his fire, watch the flicker of lightning and hear the thunder roll down off the savanna, and listen for the smaller sounds behind the thunder and drums and insects—the river, the wind in the palms, the soft songs of grief in the camp. I believe that Placide is a man at some peace with his place in the world, and when I sit on my porch and watch him hunkered on his little stool before his coals I feel something of his love and fear of the night. When he slips off to stalk crickets or make his rounds he teaches me the theory, if not the practice, of moving in the dark, and when he stops and bends his head, I listen with him and learn to make some sense of the racket I hear each night, to focus with him on distinct sounds, isolating the paddle in the water, the frog in the ditch, the footstep on the path, the cricket on the leaf.

The cricket, again. That’s what he was asking. He wanted to know I liked the roast cricket he had given me earlier, which is still in my pocket, intact and untasted. And I told him yes, it was good, it was beautiful, and yes, tasty.

Well. Perhaps I should taste it then, if for no other reason than so I can retract my statement before he stuffs my pockets with barbecued crickets. I pull the cricket out. It’s squished a little, and damp with sweat. I run my fingers over it, feeling its burnt little legs, its carapace, antennae, thorax. These are not body parts I’m accustomed to eating. But I know it’s just another arthropod, it might as well be a shrimp or a crayfish, and I’ve peeled the little boiled legs off many a shrimp without a second thought. And so, thinking of shrimp, thinking Arthropoda rather than Insecta, I put the cricket into my mouth.

It’s delicious. The flavor reminds me of shrimp, really. Shrimp, only with terrestrial overtones—the smoke of Placide’s fire, the forest leaf the cricket was wrapped in, the wet grass where it hid and sang, the night wind that blew off the river and carried its song up to Placide. I thought I would have to choke it down, but instead I chew slowly, savouring the texture and flavor, the unexpected pleasure. There’s something uplifting in the taste of this cricket, euphoric, and yes, even beautiful. At the same time an involuntary shiver goes down my spine and into my stomach, because after all it isn’t a simple business, eating my first cricket and contemplating the beauty and dread of the equatorial night, where a little girl is freshly buried, where my wife has once again vanished.

The thunder rumbles, leaves rustle, a warm damp breeze rises—too warm, too damp. Suffocating, actually, and carrying out of the forest the smell of rot and putrefaction. The half-swallowed cricket suddenly gags me, as if those jointed legs have snagged in my throat, as if a prejudice rooted deep in my guts now overrules the spontaneity of my taste buds. I stumble inside for a drink of water and end up lying on the couch, breathing fast, pulse racing, cold sweat on my skin.

Thunder and lightning crack together, and while the house is still rattling, the rain comes. I get off the couch and step out on the porch, where Placide stands on the steps in his overcoat, in the shelter of the eaves. On the tin roof the rain booms. Placide looks up at me, but it’s too dark to see his face, and the rain is too loud for talk. I go to the edge of the porch and urinate into the torrent. Thunder cracks and rolls, over and over, and lightning imprints the scene on my brain and gives it a visual resonance, so that even after I go back inside, undress, blow out the lamp, and lie in bed beneath the mosquito netting, listening to the diminishing rain and the roar of the flooding creek, I continue to see Placide’s small huddled figure, and behind him rainwater streaming off the corrugated roof, trees bending, leaves tossing, and water running in sheets and rivulets through the yard and down the hill to the swollen and rain-blurred river.

But the rain has taken the heat and energy from the night. I even seem to hear Kate breathing, deep and rhythmic as if she were stretched out beside me, but I know that’s only some distant or imaginary sound on the border of sleep. I know that Kate is crouched somewhere in the darkness, dodging leaks in a crowded hut, shrugging off the discomfort, secure in the company of women who still sweat and sway from a night of dancing, women who sing now in soft hoarse voices, urging babies wakened by thunder to return to sleep.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Editors' Prize Winner

Apr 16 2024

Invasive Species

Invasive Species We couldn’t decide between killing lionfish or common starlings. Harry voted for lionfish because spearfishing them would require a trip to Florida, a place on the map contrary… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

The Regal Azul

The Regal Azul They were somewhere over the Atlantic, south of the Grand Bahama, but beyond that, Lang couldn’t say. This absurd cruise ship, outfitted with every form of entertainment… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

Semicolon People

Semicolon People If I spent four years in medical school, I’d want people to address me as “Doctor,” so I call my new psychiatrist “Dr. Reagan” even though my friend… read more