Featured Prose | August 22, 2018

JM Holmes: The Legend of Lonnie Lion

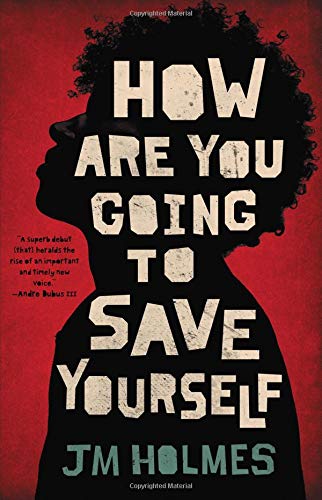

JM Holmes was born in Denver and raised in Rhode Island. He won the Burnett Howe prize for fiction at Amherst College and received fellowships at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference. He’s worked in educational outreach in Iowa, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. JM’s short story “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?” was published in the Paris Review. His story “The Legend of Lonnie Lion” appears in TMR 41:2. “The Legend of Lonnie Lion” is an excerpt from the book How Are You Going to Save Yourself, © 2018 by JM Holmes, published by Little, Brown and Company on August 21, 2018.

You can listen to our Soundbooth interview podcast with JM Holmes, conducted by TMR summer intern Sloane Scott, here.

The Legend of Lonnie Lion

by JM Holmes

Two pieces of my pops’ advice stuck with me—Don’t marry a white girl and Never pick the skin off chicken. It’s the best part. I don’t pick the skin off of chicken ’cause he was right about that. And even though it was just my pops playing around, I can’t see the first piece of advice sitting well with my mom, Nicoletta.

Lonnie Campbell could run so fast. Lonnie could hit so hard.

My pops was big enough to block doorways, and Mom was small enough to almost fit her whole body into one of his pant legs. It’s hard for me to imagine them together. They met back at the University of Washington. She was his tutor, the type of tutor who wrote essays for players on the Huskies football team to pay her tuition. Pops grew up an army brat and spent some time on Fort McChord when Big Daddy, his own pops, was stationed there. It made sense for him to stay in Washington. How my mom, an East Coast girlie, ended up in Washington, I don’t know. She doesn’t speak much on it but still yells “U Dub!” every time she sees someone rocking the gear, and I shake my head.

He left the university a year early to turn pro. Mom was a year ahead so it worked out. He was a D-end, first for the Tampa Bay Bucs and then for the San Francisco 49ers. My mom took the football bread that was coming in and became a self-taught architect and real-estate developer. She made some investments, made money, at least, that’s how she tells it. But she had Italian hustle like that, so I buy it. I don’t know many stories from the bliss times. I know that she played tennis well, and after I was born, my pops got a few sets in with her every day so she could lose that baby weight and get back in shape. Afterward, they’d bike through the burnt-out California hills, those rose-gold, cracked slopes that jutted up between the houses and kept all the lives private. My pops is fat as shit now.

I was around six when they split—before I can really remember. His body was too shot to keep playing football, and he left to try and make some moves in LA for a bit. Mom got us a studio in Koreatown to stay close. For reasons I didn’t understand, the money was all gone. My mom and I slept in the same bed together with a baseball bat next to the nightstand. No one ever broke in, and Pops never came back.

After LA had squeezed him for the last of his football dollars, Pops moved back up to Washington and had a kid, my little sister Whitney, with his high-school sweetheart. I was around nine then, and our communication went radio silent for a while. My mom and I came east to Rhode Island to be with her mascarpone-colored family. But some years later, when I was old enough to fly alone, she would still send me to visit my pops, would buy the plane tickets and drive me to the airport. She never tripped over the lack of child support and even smiled each time she walked me to the security line. The smiles were always nervous—Come back you, the you I’ve been building for years. Come back the way I’ve made you. Pops would send me home with my suitcase filled with FUBU and Coogi off the discount-clothing racks, clothes my mom accidentally ruined in the wash.

The summer I was thirteen I clocked the Sea-Tac Airport for the first time. Pops was waiting at the gate in beat-up loafers and sweats. That’s the way he rocked, comfortable. He had long since lost his celebrity status in the city as a football star. Back in his playing days, he used to wear suits to games, but I guess sometime after the lights dimmed and the yelling stopped and the bones in his battered knees ground like pestles into mortars, he wanted something more forgiving.

His massive frame drew stares as he scooped me up. I tried to keep my feet planted, play it cool, but it’s hard to resist a forklift. In a too-loud voice he said, “Let me smell ya, make sure you’re my cub.” Then he dug his uneven beard into my neck and made snorting noises. I laughed despite myself. He let me down, said I was the right one, and we left those people at the gate.

After he threw my suitcase in the trunk of his old DeVille, he squeezed himself into the driver’s seat and started the car. I brushed some cracker crumbs off the leather and put my backpack next to Whit’s car seat in the back. Pops was a shitty driver. His legs were too long and got tangled beneath the wheel. He got his license revoked later, but not for that. After he turned the radio on, he accelerated into horns and oncoming traffic.

“So what kind of music you into now?” he asked.

“Rap.”

“C’mon, G-Money, you gotta tell me more than that. Who you listen to?”

“I dunno.”

“What you mean, you dunno?” he mumbled, trying to clown me.

The state was growing greener as we headed south on I-5 toward Olympia.

“I like Dipset,” I said.

“You ain’t listen to my man Ricky Ross?”

“He’s okay.”

Pops looked over at me—the car swerved a little. “You know, if I was a rapper, I’d be Rick Ross.”

I nodded.

“You know why?”

“’Cause you’re both fat?” I said.

“You think I’m fat? Your cousins call me Uncle Love Biscuits. I only stay big for them.”

“Okay,” I said.

“If they didn’t like it, I’d be lean and fast as my playing days. They used to call me Lonnie ‘Lion’ Campbell.”

“Dad, you look more like a rhino.” I blew out my cheeks like a puffer fish.

He stared over at me real serious. “You don’t believe me?”

The highway got wider once we were south of Tacoma, and the people drove slower. I liked when my pops talked about his NFL days. He got animated and used my name for dramatic effect—Gio, G, G-Money, or, when he told his tallest tales, Giovanni.

“Are you dunking yet?”

“I’m thirteen.”

“I was dunking by thirteen,” he said.

“Sure.”

“I could still dunk now, G, that’s God-given. Just ’cause I got some fat on these muscles don’t mean the muscles ain’t there.”

I looked over at my pops, who looked like a chocolate sundae drenched in caramel the way his tan sweats rode up, stuffed into the driver’s seat of the DeVille. I broke out laughing. My pops was funny when he lied. Maybe that’s why he got away with it his whole life.

My stepmom, Dee, Pops’ second woman, or the second I’d met, smoked cigarettes. They were brown and longer than straws, and she’d stand outside forever in the summer breeze burning them down to the last. We got along all right as I grew a little older. Pops and I were still drifting back toward each other and I wasn’t going to let anyone mess it up. So on Sundays, to bond, I would even ride with Dee an hour to the Indian reservation, where she could buy her cartons tax-free. But back in the duplex, whenever she left them on the counter, I’d hide them in the big vase near the front door. There must have been thirty packs in there she never found. She used to bitch and blame my pops. He never yelled at me, though. He didn’t want her to smoke anyway, and I just wanted to be a punk.

Two years later, the summer I was fifteen, I saw Dee walk out of the bathroom in just a towel. I’d been watching preseason football on the TV in their bedroom ’cause that’s where the cable box was. She walked like she deserved everything and let her towel fall in front of the mirror. She was the right kind of full. The girls at my school were starting to grow up, but her figure still looked alien—her hair in two long braids that almost reached her ass, which curved and sat in place thicker than a basketball.

“Jay Stephens used to come by the house when I was in high school,” she said, nodding toward the TV, her voice hissing like rain on a campfire.

I didn’t even turn back to see who she was talking about. Before I had a chance to take it all in, my little sister came into the room and jumped on the bed with me.

“Put Lilo on,” she said.

I changed the channel to Disney. The smell of beeswax came off her hair.

“You just get braided?”

She smiled and whipped her braids around, letting the beaded ends bounce off each other. “Audrey says I’m gonna be a heart taker.”

“Heartbreaker.”

But she wasn’t listening to me. The Jonas Brothers were on the TV. She loved kid pop stars like her mom loved athletes, and I prayed she didn’t grow up to be a groupie.

Then my pops walked in, big and calm. He smacked Dee’s ass and it rippled like a pot of hot water before it boils.

She pushed him away. “Not in front of the kids!” She wrapped herself in the towel again.

“What?” My pops had a hoarse laugh that came from deep inside him. He grabbed her around the waist and she pushed him away again. Then he caught me watching. “C’mon, G-Money, don’t act like you ain’t never seen one before.” He laughed again.

I looked back at the cartoon. “I seen plenty,” I said.

“Boy, you ain’t seen none,” Dee said. Then she dropped her own laugh on me, and I shrank inside.

“Whitney, show your brother the new paint job in your room,” my pops said.

“I wanna go to the store,” I said.

“And?” he said.

“Let me use the car.”

“Let me see your license,” he said.

“Mom has me drive.” That wasn’t a lie. She’d let me get my permit early, but every time in the car with me, she still sweat the whole ride like the next hog in line.

“You better start walking,” Dee said.

They were already fooling around by the time I got up and took my sister out of the room with me.

Whitney didn’t play sports. At age five, she was all diva already. The walls of her room were painted light pink and periwinkle. My pops had painted the walls twice, but he painted them again when she didn’t like the shade of pink. She spent the next hour showing me her toys, and I fell asleep on her bed surrounded by stuffed animals.

My mom and I had moved around Rhode Island a lot while she got certified and chased teaching jobs. She stopped developing real estate, said it was ’cause she wanted to be home more, but I think there was no more football money. In small-town middle schools, I fell in love with some freckled girls in light-up sneakers, wasted my lunch money on giant Hershey’s Kisses for them—Dee would’ve called me a trick. Even when the kiddie-love dates never seemed to work out, my age kept me ignorant to hate-eyed parents. Mom said nothing and kept us moving, looking for a better place.

When I got to high school, I fell hard for one Saba Thomas, a light-skinned Cape Verdean girl who had my nose wide open. My mom tried to keep me safe from the blaze. She didn’t like when I hung out in neighborhoods like Saba’s—everything in Spanish or Portuguese, police curfews, kids all ages mobbing on corners. She was always confusing safety for happiness. She still is. But she tried to like the girls once I brought them home.

The only girls I brought home were ones my pops would’ve said had “the potion.” He would try to move his hips like a merengue dancer and tap his ass while he said it. “Campbells can’t fight the good potion,” he said. I still remember that. I still think about Saba.

She liked my voice. “You talk so sexy,” she said.

We had How High blaring out the TV to drown the sounds of us flirting and drinking. Still, I listened for her mom moving in the next room.

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, say something.”

“What do you want me to say?” I felt like I was whispering.

“Anything. Surprise me.”

“What do you mean, anything?”

“Jesus, just shut up,” she said.

I never had game. I went to kiss her and she lay back on the couch, playing like she was trying to avoid me. Back then, everything happened on couches. Bedrooms were never vacant. She shared a room with her little sister, and her mom and step-pops had the other one, even though he was never home. Her skin was almond, and the shape of her gets fuller the longer it brews in my memory. I remember her hips hatching out of her jeans and the soft lines of her slender shoulders.

“Won’t your mom wake up?” I said.

“My mom’s a drunk.”

“Drinks don’t put me to sleep.”

“Then you don’t drink enough,” she said, and kissed me. “Are you drunk now?” she asked.

“Should I be?”

She puckered her lips at me. Her skin stretched tight at her temples like a drum. I looked down at the empty pint of rum we’d gotten from the A+.

“I’m tipsy,” I said.

She bit me.

“Fuck!” I said.

“No, you’re not,” she said and got up off the couch. She took off her shirt in that cross-armed way, exposing her smooth beige skin. In only her panties, she walked around the wall to the kitchen. I followed but trying to slide in slow, like my pops. The kitchen was a narrow strip separated from the TV room by a table. I was tall enough to see on top of the fridge, where her mom hid the box of Fruity Pebbles from her younger sister. Saba went for the wine rack on the counter and pulled a bottle with a dusty French label.

“Damn, that’s old,” I said.

“It’s my grandmother’s.”

She grabbed a bottle opener and uncorked the wine.

“Really?” I asked.

“Stop being a pussy,” she said. “My mom won’t notice.”

She drank from the bottle in deep pulls, spilling enough that it ran all the way from the corners of her lips and down her neck and chest to her stomach, staining the white edge of her underwear. The green stripes, dark and fine, didn’t show it as much. I tried to take the bottle, but she held on to it and danced around—curves and hips and black hair.

“Here.” She handed me the bottle and kissed me with purple lips.

I sipped it.

“Drink it,” she said.

“I’m good,” I said.

“I didn’t know you were such a bitch.”

I tipped the bottle back again. The wine was sweet and warm.

“More,” she said.

I drank till there were only sips left to swirl at the bottom and set the bottle down. She grabbed my cold hands, lifted them up, and twirled underneath my arms. She moved in circles with her waist—her eyes took everything into their black. We danced for a while in silence. I started to feel warm in the fingers and bent down and lifted her up.

“Good,” she said, and she kissed on my neck.

I let her down and she opened the door on their third-story porch. She flung the empty bottle over the railing, and the glass shattered across the parking lot with a pop.

“Ay, maricón,” someone yelled, looking up at us.

“Yo, no speaki español.” She smiled and grabbed below my belt. I smacked her ass. She was too thin to ripple.

After promoting boxing, he took a shot starting a clothing line, then a recording label. It all went belly-up, and the football money was gone, so my pops started cleaning office buildings at night with my uncle Bull, his brother-in-law. He claimed my mom resented him for not taking the NFL insurance money when he had the chance, but she never said as much to me, and, to her credit, even when we were living off my grandmother while my mom went back to school, she never came after my pops for the piece of nothing he had.

The days after his night shifts, he’d sleep till dinner, so I wound up spending more of the summer with my sister and Dee than with him. I grew to like Dee. She acted younger than she should have, but my pops did too, so it all failed just right.

During the summer after my sophomore year, she started talking with me about weed and tattoos, and I thought that was cool. One day, she finally worked me up into wanting a tattoo, then said she’d take me.

The whole way there Whitney talked about all the tatts she was going to get when she was old enough. She was only seven. Dee said nothing, blew smoke from her long cigarette out the window, and laughed hollow like she was far away.

The spot we pulled up to wasn’t a shop. It was a house. Dee had called twice on the way but no one had picked up.

“Maybe he’s busy,” I said.

“We’ll wait.”

The town house had a bunch of cars out front.

“We could just go to a real place,” I said.

“Stop acting shook.”

We walked up to the front door and rang the bell. A dude with good tattoos on his neck and arms and the worst tattoos I’d ever seen on his legs answered.

“Yeah?”

“Mando still here?”

“Who’s asking?”

“Tell him it’s Deandra.”

“Aight, hold on.” He disappeared into music and barking.

A short, dark Asian came to the door next. “Damn, Dee, look at you, still fine as hell.”

Dee laughed and they hugged. “How are things?” she said.

“Aight. It’s been a little tough since I lost the shop but they still spread the good word.”

“I can see that.” Dee glanced back at all the cars on the lawn. “You look real busy.”

“Nah, half these cars are just sack chasers here to buy movies from Quintin.” He stared out into the yard at his grass burnt brown from the summer heat. Then he looked at the sky like he was waiting for rain and the cool northwest breeze that blew when the sun started to go down.

“How long’s the wait? My kid wants some work done.”

“Little Whitney?” He smiled.

“Boy, stop. Lonnie’s kid.”

Mando looked me over like I was an inkblot test. “Okay. I gotta finish up homeboy that’s in the chair now and then I can hook him up.” He moved aside and we all walked in. The walls inside were hung with modern art, and 808 drum kicks pulsed from everything. Muted music videos were playing on a box flat-screen TV, and the two leather couches were packed with people. Mando got jittery for a second. “Ay, ay, ay, turn that shit down,” he said. “We got kids in here now. Put that dutch out too.”

“I just sparked it.”

“Fuck, nigga, then take it outside.”

I wanted to tell them they could smoke inside. I wanted to evaporate into the tree clouds with them. To the left of the couches, away from the TV, a man lay facedown on a table with towels taped to it. The towels had been white once but were now smudged across with black ink. Mando’s fingers were eternally black. He reached to pick up the needle and shuddered, then went to the bathroom for a long time.

I sat and looked at the binders of his work. Unlike most artists’, Mando’s had no photos. The binder was filled with paintings and sketches and notes on napkins.

The man with the bad and good tattoos came and sat next to me on the couch. “He’s nice, right?” He pointed to the binder.

“Yeah, dude is real nice,” I said.

“I don’t think you appreciate—Mando’s a fuckin’ maestro, kid.”

I fixed my eyes on his bad tattoos, but the way he kept tapping his feet moved their uneven lines, and it made me sick.

“What’s with those?” I said, pointing to the half-sketched faces above his knee.

“Oh.” He laughed. “He’s teaching me. These are my practice runs.”

“You couldn’t get a dummy or some shit?”

“Mando believes in learning on the job. That’s how you get nice. Not with fuckin’ dummies.”

I wanted to ask him if he knew that his shitty tattoos were permanent, but his eyes bounced around like something was pressing them out from the inside. He made me nervous.

Mando came out of the bathroom and closed the door behind him. Whitney sat on a plastic folding chair playing on her chunky red Game Boy, and Dee had squeezed herself between some dudes on the other couch. She was rocking the Cleopatra weave those days, and the men were licking their lips and leaning too close.

Soon enough, Mando was done and the man got up from the raised table. He walked over to the mirror to inspect the deep black lines of a crucifix that seemed big enough to weigh him down. The Jesus was tragic and Latin-looking. The cross was beautiful and seemed to raise off his back like it was somehow leaning above you even if you were looking down. The whole picture came off graceful, even with the deep, painful lines of Christ’s wounded body.

Mando came up to me and nodded toward the table.

I walked over and Dee got up from her fans and followed.

“What do you want?” Mando said.

“‘People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.’”

He cut his eyes at Dee. “You didn’t tell me all he wanted was a quote.”

“In script,” I said.

Dee stared at me. “I didn’t know,” she said.

“This shit’s a waste of my time.”

“Why don’t you get some art?” Dee said.

“’Cause I want a quote.” I couldn’t think of anything else I wanted.

He sighed. “What is it again?”

“‘People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.’”

He glanced at Dee. “Where the fuck you find this kid?”

“I don’t know. He’s Lonnie’s kid. He’s half white.”

They laughed.

“You’re open.” Mando shook his head. “Who said that?” he asked.

“James Baldwin.”

“Who?”

I was silent for a while, listening to them roast me.

Then Mando got real irritable again. “I ain’t dealin’ with this shit,” he said.

“Relax,” Dee said.

“It’s a waste of my day. I, I, I try and do you a favor—” He stormed off toward the bathroom.

“Again?” she called after him. “Right now?”

“What? You want some?” He smirked at Dee like they shared an inside joke.

She shook her head and he disappeared into the bathroom. Dee was vexed and just stared at me. I thought we shared a storm, but I guess that didn’t matter here. I wasn’t her blood.

I imagined my pops sliding through the front door and freezing the room. People would look at him and then he’d come throw his paw on my head a little too strong ’cause he didn’t know any better. People would think, Damn that’s a big nigga! And I’d smile ’cause I knew what they were thinking. He’d slap Dee’s ass again and tell her to wait in the car. Then I’d tell him the quote I wanted and he’d say, Man, G, that’s real cold. Keep your head in them books. I’d smile again, the biggest one, from my gut, because I was going to write our history—history of our pride, lions of blackness in all our shades.

No one burst through the door. I ended up getting a tattoo of Jesus walking on water, just the outline, with light shading, after an Alexander Ivanov painting I’d seen online once. It took Mando three hours and it hurt like hell and I wanted to cry because the needle felt like it was scraping my ribs below my chest, but he just kept moving. Even though he had glassy eyes and seemed to tweak a lot, his fingers stayed steady, and then he was done.

When we got back home, Pops was in the kitchen eating cold pizza. He was going to work in a few hours, but I asked him if he wanted to play ball anyway. He said he was tired and I told him I knew he couldn’t dunk. He just kept eating.

“I got a tattoo today,” I said.

“Oh yeah?”

I lifted my gray shirt, which was stained black on the inside from the ink, and showed him the art going from my chest down to my ribs.

He opened up the fridge, took out some fruit punch, and drank it straight from the bottle. “Keep it Christian,” he said and laughed, and that was it.

I called my mom and told her. She cried for a long time Why’d you ruin your beautiful body? she asked. Why’d you mar yourself? Then she cried awhile longer and told me to move out here if I loved it so much, and I said I would, Pops would be happy to have me. We stayed on the phone for a bit in silence. Her breathing finally calmed down, and she said she loved me and hung up.

The next morning, I woke up to yelling from their bedroom. “You took him to that crackhead!”

“Shut up, Lonnie. He’s not a fuckin’ crackhead.”

“Deandra, niggas who smoke crack are crackheads.”

“You would know,” Dee said.

I never knew my pops to raise his hand to a woman, but I heard something break. There was some more shouting and then the garage door opened. I lay awake on the air mattress until the sun broke through the brown blinds on the window and spilled out across the white sheets. Some manila folders had fell from one of the storage boxes next to the bed. I pushed them off my sheets, rolled to face the wall, and waited until I heard the peace of frying bacon. It was Saturday. Pops left again and came back around midday with bagged eyes, smelling like hot-dog water instead of bleach. He took one look at me, gloss-eyed and cloudy. He looked away and went into his room before I could chop it up with him. I waited up as late as I could that night for him to wake up. I fell asleep to the sounds of summer-league basketball coming from the TV in the other room.

Leah came during my junior year in college. The girls before her faded, and I started again at one.

July was hot in Ithaca, and the heat came in damp from storm clouds, turning my dorm room into a sauna. Leah sat on the edge of my bed. We were fresh from a cold shower and already starting to sweat. I sprawled on my back letting the last few drops of water air-dry. Her eyes scanned the room like a mother’s eyes. Her brown hair hung wet and clean down to the middle of her back. As I got up, she asked where I was going. I gotta work, I said. As part of the scholarship, I had to coach basketball camp for at-risk kids in Ithaca. Aw, my baby giving back, she said. I pulled on a pair of basketball shorts. Gotta sing for my supper, I said. Stop complaining, she said, brushing some crumbs off the corner of my mattress, her hands pale against the maroon. And change your sheets, she said, then smoothed the edges tight and flat. She liked to smooth and fix and make things neat, molding with her narrow fingers calm and knowing, the look in her eyes soft—Let me help build you. She lay down and patted the bed next to her. I pressed into her and she draped an arm across my stomach. Her limbs were long and smelled like soap, the soft-scented bar kind, not the mango-cocktail gel shit.

I had to go soon but didn’t want to move just yet. She traced her red nails around my tattoo, her hair heavy and warm across my collarbone. Her fingers moved along the outline of His robes, and I asked, “Why’d your people kill Him?”

She smiled with her deep brown eyes and kissed below my chest, where His head was engraved. “’Cause it made for a good story,” she said. She licked up to my nipple and I pushed her head away. “I didn’t know you were even religious,” she said.

“I’m not, really, I started. It’s mostly my pops’ side. They all sing in the choir and do the gospel thing. My pops had two choices—preacher or ball player.”

She moved her face up till her lips rested in that soft spot below the jaw. The spot that made me want to taste her. “I’m sure he had more than two,” she said.

I didn’t feel like putting her onto my history, so I was silent.

She looked across the room at a picture of my pops in his NFL uniform. “I guess he made the right choice,” she said.

It’d been almost five years since I’d seen him last. My mom said he wasn’t the same. More than his body had been banged up. I thought about the shadow-quick phone calls. I hadn’t heard much from Dee or Whit either. No one wanted to speak on it. Without naming, Pops’ troubles remained minor.

“Yeah,” I told Leah. I couldn’t put his unraveling on the NFL like my mom did.

“He is huge,” Leah said.

“And I’m not?” I said.

“Not that big, you’re not,” she said.

I pretended to bite her nose and she scrunched her whole face up.

When she left that day, I watched her from my fourth-story window, watched her stride away to her business as the wind from the coming rain shook the maple leaves and obscured her image. I watched her walk up Highland Avenue as long as I could, until she bent around the corner and I lost sight of her.

She wanted to meet my parents. My mom would have loved her because she could only glance at women, at people in general, always confusing security for a life fulfilled. I think the trauma of the divorce and Koreatown was still with her. After Saba’s parents and a few others’, Leah’s mom and dad would’ve looked like salvation. They were both professors out in Denver and would’ve signaled peace where there was none, at least not in my vision. The way her mom looked at me and a few of the PhD students. When I’d visited, her parents had a group of us over for dinner, and her mother let her eyes linger too long on a couple of the young men, made comments about what we were wearing, asked me how tall I was, said she loved the basketball build, then got dreamy like she wanted a night away, or maybe a few, from the life she’d made. But then she’d go back to talking about the politics of cleft states, and everything returned to normal. Her dad looked at me a few times like he might’ve caught it too, and then after dinner, I heard them whisper-fighting in the den. I kept my ear open to the lessons—hoping history wouldn’t repeat itself.

Leah’s eyes wandered just like her mom’s. When I’d call her on it, she’d say, Aw, you’re jealous, or Relax, tiger, and I imagined she’d learned how to manage men from her mother too. My mom had loved my dad every day for fourteen years since the split, without cease. At least that’s what she claimed. I guess she was romantic like that, but it’s always easier to love a memory.

One time, at her place, after I rolled her out, Leah sat on my ass and blew on my neck. I didn’t mind cuddling in her bedroom. It had pastel-colored paintings and scented candles, shit that gave you a cuddly feel.

“Stop,” I said.

She put her face down next to mine. “You know you like it,” she said.

“Why don’t you give me a back rub?” I said.

“Who do I look like?” she said. “You should give me one.”

“Girl, I’ll rub every inch of you,” I said.

She laughed and turned over. “Go ahead.”

I started up at the base of her skull, real gentle with just one hand. Then I kissed in between her shoulder blades and started kissing her sides and hips.

“Really?” she said. “That’s as far as you’re going to make it?”

I flipped her over real quick and started biting her stomach. My teeth marks were bright red in the flesh next to her hipbones.

“Stop, stop.”

I looked up at her.

“Come here,” she said. She tossed the hair off her shoulder and I lay my head there. “Are you going to let me meet your parents soon?”

“Damn,” I said, “you really didn’t want to fuck again, huh?”

She rolled her eyes at me. “You’ve met mine,” she said.

Wandering eyes aside, they had seemed to sparkle in their suburban home near Denver. Truth be told, I imagined it was a lot like the California suburb I’d been born in while my pops still played, before the 49ers did him dirty. Leah’s family had a fire pit out back and the whole family did dishes, synchronized like they were running a motion offense. Then we all sat and watched late-night television. Shit, I could almost envision them caroling together even though they were Jewish.

“And?” I said.

“And I want to meet them,” she said. “They won’t scare me away.”

“That’s not what I’m worried about,” I lied, and I went down to kiss her inner thighs. She closed her knees and I rested my head there, gazing at her. She laughed and pinched her face up the cute way she always did. “Put your glasses on,” I told her.

“Let me meet your parents.”

“Fine,” I said and spread her legs. “Now put your glasses on.”

The moonlight that shone through her lace curtains was pretty on her skin. Her hair was sprawled on the pillow next to where I’d been beside her. I wanted to lie back down and smell her hair again. I wanted to fog her glasses and kiss her thighs, and I really did want her to meet both my parents. Our kids would be little JAPs with traces of nigga in them and have soft hair and beautiful eyes and smiles.

I didn’t ever talk about my family. All she knew were the pictures in my apartment. I even had a few from when I was little, when we were still all together. Maybe she made assumptions about my folks because her parents had worked so hard on their love, like homemade-chocolate-covered-strawberries type love, like surprise-love-poem type love, like Marvin Gaye–vibrator–Jacuzzi-session type love. But I knew the small fractures in her parents’ bond, even if she didn’t want to see or hear them.

That night, after she fell asleep, I packed up my overnight bag, got in my car, and left. I drove all along the shore of Cayuga for a while, heading nowhere, with the image of her sleeping sound stuck like hooks in me, ripping at my insides. The lake was much prettier at night. I parked by the falls in the state park and picked out some town lights across the way.

It would be three hours earlier in Washington. I hadn’t heard from my pops since I graduated high school, but I tried the numbers I had anyway, once on his cell and once at home.

Dee picked up and told me he hadn’t been around in months. The world felt on a loop.

“He isn’t picking up his cell,” I said.

“New number,” she said.

“How’s Whit?”

She sighed deep like she had a story. “She’s asleep already.”

“He still come around?”

“Boy, some things you gonna have to ask him yourself,” she said.

I asked for the new number.

“Hold on.” Her voice sounded a thousand packs worse and crackled through the earpiece. She gave me the new number and hung up. I called three times, and each time a man picked up and said he didn’t know a Lonnie. Stop calling.

A few days after I’d gotten my tattoo, Pops said we were going to Burlington Coat Factory to get me jazzed up, but before we even hit the highway, I saw my bags in the backseat. He was taking me to the airport a week early. It was like something was all used up, like we had stopped building together all of a sudden. That was the worst of it. I wondered if we’d ever start again. My ribs still hurt like hell as we walked through the totem poles of the Sea-Tac Airport in silence. They stretched up, towering over him. Faces like legacies carved into trees that had once jutted up into the blue northwest sky, preservations of family histories, legends incarnate. I loved that word. The word was big enough to fill the universe—legend of the sun and moon and stars. Family legends, so many lost.

We were late, and his strides were long. I had to trot to keep up.

“C’mon, G,” he said. I bumped into people as we went, my eyes fixed on those etched histories. “Gio!” he said.

“I can get it erased,” I said.

My face got hot. I tried to stop, but he grabbed my wrist and yanked me through the crowd.

“Dee told me to get it,” I said. “I just wanted a quote.”

“It’s not about the damn tattoo.”

I saw a fast-food Chinese restaurant and thought it was my last hope. “Can we get some food? I’m hungry.”

He eyed the Panda Express, then checked his watch. We stood still and silent for a moment. He was probably thinking about egg rolls and lo mein and thinking about them hard. But then he started to drag me toward the gate again.

I must’ve asked why a dozen times. He kept yanking my arm until my shoulder hurt almost as much as my ribs.

“You have to go home,” he said.

Home hit me like a fist, and I stopped asking.

When we got to the check-in, he confirmed the ticket change. The attendant said I’d be able to get on. He smiled at her, and there was a little fear that crept behind her green eyes. It was some of the prettiest green I’d ever seen. He saw the fear too so he said, “Thank ya kindly.” Then she smiled back. My pops knew how to turn the black folk on when he wanted to.

He gave me five dollars to get some food during my layover in Chicago. I wanted to tell him that I knew that just like the ticket, it was my mom’s money. Instead, I hugged him goodbye. I could feel the sweat beginning to soak through his gray shirt.

There are pictures in my mom’s house of them on vacation in San Diego. His shirts hang like dresses down past her knees. She looks happy in those pics. They both do. He is the happy ghost in those pictures. A happy black ghost with my smile.

By the end of that summer before I returned for my senior year, Leah had quit calling. When I didn’t respond to her messages, the texts and e-mails stopped too. My pops hadn’t resurfaced. Dee and my mom had been bitching at each other about it on the phone for weeks. I wanted to call Leah every day, apologize, tell her what was up, but it was unfair to leave her with two options—pity or bullshit.

I was back at my mom’s, eating soup and watching the light change through the window. Fall was coming. The sun was crisper and not hazy like the shimmering heat of summer. My mom and I looked at each other across the kitchen table, in silence. When the home phone rang, somehow we both knew.

She answered it. Her voice was hushed. “Yes, he’s home. Lonnie, he’s been calling you and he—” Her voice was rising, and he must’ve cut her off. “Yes, I’ll put him on.” She walked over to me with eyes so full they would have burst if I hadn’t smiled and slouched back in my chair.

“Soup’s good,” I said.

“It’s your father.”

“I’m not here right now.” But she looked like she would crack again so I took the phone. “Ayo, Pops.”

“What’s up, G-Money, heard you tried to call me a while back?”

“Yeah, glad to hear you livin’.” He wheezed into the phone and I felt bad. “You been running?” I asked.

“What?” he said.

“Never mind.”

“I was calling to check up on you,” he said.

“Ray,” someone yelled in the background on his end. “Ray!”

He muffled the phone and said something to the dude yelling.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“G, lemme call you right back.”

“Yeah,” I said, but there was already a dial tone. I looked at my mom. “Graduation is in May. I’ll give you the date when I know,” I said. “Take care.”

The operator’s voice began to play and I hung up.

A few years later, my cousin finally told me he’d been staying in a funky spot down in Rainier Vista. He didn’t use his real name around the folks he was staying with. The fat nigga had gotten Ray off a bottle of Sweet Baby Ray’s barbecue sauce, so that’s what he went by. Ray “Lion” Campbell didn’t have the same ring, though. I didn’t know if he was working or what he was doing. He didn’t even check up on Whitney anymore.

SEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Featured Prose

Apr 19 2024

An Interview with Robert Long Foreman

Recently, TMR intern Shayla Malone interviewed Robert Long Foreman about “Song Night,” which tells the story of a pot-smoking father who has to adapt to the fact that his teenage daughter… read more

Featured Prose

Mar 22 2024

“Vegetable Stories” by Rohini Sunderam

In Rohini Sunderam’s “Vegetable Stories,” first published in TMR issue 45.3 (Fall 2022), an unconsummated romance buds, flourishes, withers, and endures in dormant form for two people who communicate their feelings… read more

Featured Prose

Mar 15 2024

An Interview with Genevieve Abravanel

Recently, TMR intern Shayla Malone interviewed Genevieve Abravanel about “Wilderness Survival,” which tells the story of a recently widowed mom and her young daughter, who becomes an avid follower of a… read more