Blast | March 15, 2022

“Years of Vanishing Completely” by JP Gritton

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features fiction and nonfiction too lively to be confined between the covers of a print journal. In his essay “Years of Vanishing Completely,” JP Gritton recounts how anxiety over the success of his debut novel and a daily practice of googling himself led to him discovering an artist namesake from another place and time.

Years of Vanishing Completely

JP Gritton

The beginning of this story is always a little hard to explain, so I’ll tell you the ending first. The story ends in my office, which is on the fifth floor of a Gothic revival building on the campus of a university where I’m an assistant professor of creative writing. I want to tell you that the trees stood naked and gray through the stonework of my office window. I want to tell you that it was a cold day, and threatening to rain, and that I had biked to campus in a faint drizzle, into the very teeth of the wind. But the truth is that all this is guff, window dressing, artifice. The only thing I can remember from that day is checking my email.

Like most teachers, maybe, I’m surprised when I get an email from anybody other than a student. I was pretty sure I’d never had any Stephans in my class, and certainly no “Stéphane,” with a little black beret over the first “e.” When I opened the email, I was more certain: “Cher Monsieur Gritton,” it read, “c’est avec plaisir que je réponds à votre demande.” I don’t teach French; I never have, and so for a moment I sat before my computer, my eyes sprinting over the sentences I only half understood.

And then, very dimly, it all came back to me.

I’ve put off telling you the beginning of this story because it’s embarrassing. About a year earlier, around the time galleys of my novel were going out, I’d heard from a friend of mine that a book has about a three-month window to become “a success.” This friend of mine is a writer, the kind of person who’d know. But if I’m honest, I wasn’t sure what counted as “a success” or how I would know if my own book were “successful.” When my novel came out, anyway, googling my name seemed as good a way as any to find out.

I’m embarrassed to tell you this. I’m embarrassed to explain that for about three months, I began each day by googling the words “JP Gritton”—my own name, that is. I’m embarrassed to explain how badly I needed the top hit to be a gushy review of my novel in the Times (LA, New York, London; I wasn’t picky), or the Chronicle or even the Globe. I’m embarrassed to admit that when I found no such review, I began googling unlikely variations of the spelling of my name: “J[space] P[space] Gritton,” for instance, or spelling Gritton without the second t that separates it from Gritón, which is Spanish for “he who yells.” I’m embarrassed to admit that within a couple months of my book’s publication, it had become my habit to perform a standard google search of my name, followed by a google news search, followed by a google image search. I’m embarrassed to admit all this, but that’s how the story starts. That’s how I found the goat.

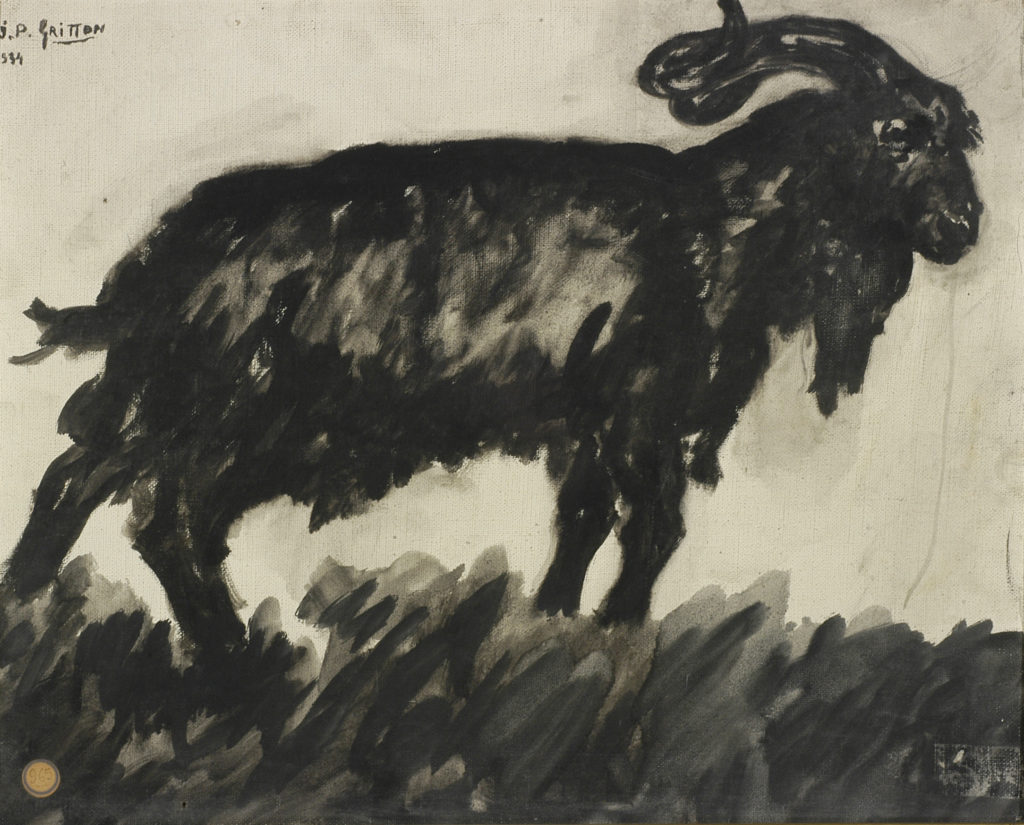

This would’ve been about December of that year, maybe a month after my book dropped. Sandwiched between my toothy author photo and the graphic on the cover of my novel was this painting with my name on it. J [period] P[period] Gritton, plain as proverbial day, right there in the top right-hand corner of the canvas.

It was a pretty good painting, too. Do you know that way certain images can represent not a thing but a mood? Like da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is not a portrait so much as a mysterious smile. Like Picasso’s Guernica isn’t a city in Spain but a horse screaming among flame and ruin. This goat was the same way: it was not a painting but an eeriness, an uncanniness, hair rising on the back of my neck. Dagger-sharp legs, Mephistophelean eyes, malignant horns curling from the head like smoke.

The insane thought occurred to me that it was my painting, that somehow I had done it, back in high school or something and then—I don’t know—forgotten about it? But when I enlarged the image, I saw the date next to my name.

The year before he painted that goat, in March of 1933, a dozen of J. P. Gritton’s charcoal and pencil sketches had appeared in La Grand’Goule, an arts-and-culture quarterly based in Poitiers. Of J. P. Gritton’s work, editor Raoul Jozereau gushed, “Here you will find a croquis in which there appears no evidence of naïve effort.” On the contrary, says the editor, only a supple vitality. From Jozereau, this was high praise: by the time he penned his first rave review of Gritton’s work, the critic had sat at the helm of La Grand’Goule for four years. Guest contributors to his magazine included Fernand Serreau and Henri Lejeune, instructors at the École des Beaux Arts de Poitiers and successful artists in their own right. In 1933, even as Poitevins would’ve felt the first great tremors of a global depression, a copy ran around twenty francs—seventeen bucks in today’s money.

That first feature on J. P. Gritton consisted of about a dozen charcoal and pencil sketches—a fencer thrusting, a dog pointing, a pair of soldiers grappling, tumbling to the ground—underscored by Jozereau’s breathless praise. At the article’s end, they ran a black-and-white photograph of the artist himself. In it, he’s this sad-eyed kid with black hair and a shy frown. He’s dressed in a poncey sailor outfit, like one of the Roosevelts. He looks young because, when the photograph was published, he was young: in March of 1933, J. P. Gritton was a nine-year-old schoolboy.

I’ve never been to Poitiers, but from Google image searches I have acquired a vague impression of castle keeps of white marble, downy clouds frolicking like sheep across fields of azure. A landscapist’s city, in other words, one of those idyllic French towns that seem conjured out of dream or hazy memory. And that’s what jumps out about the kid’s art, all these years later. A playfulness, an obvious pleasure in the labor itself.

“He works in complete freedom,” wrote Fernand Serreau, in the December of ’33 edition of La Grand’Goule, “for the sheer physical joy of it, without losing the calm of a child’s soul.” For Gritton, who was Serreau’s student at the École, art was a kind of game. And many years later, long after La Grand’Goule had folded, long after Serreau and Jozereau and LeJeune were gone and forgotten, I would find myself wondering if “talent” were even the right word—or anyway, the only one. Raoul Jozereau might’ve been right to call J. P. Gritton’s a “natural” ability for finding “the expressive trait,” and he might’ve been correct in asserting that his charcoals somehow capture “the attitude, the soul.” But I think he kind of missed the point. Gritton had something better than skill, something that I envied in him, now that my own art had blurred into my vocation. He had a total lack of self-consciousness. An ease in his work. A joy.

I’m not sure what J. P. Gritton would have made of Jozereau’s article, but I remember what it was like to be nine. I suspect that the novelty of seeing his drawings reproduced in a magazine soon wore off. I suspect his attention strayed to—who knows? Something else, anyway. A comic book, a serial playing on the radio, the math homework he had forgotten on the kitchen table.

It’s weird how youth, like age, can put a thing into perspective. As I read all those grand-sounding words, I detected something odd, even morbid, in all the praise, which is a word that comes from Old French, preisier, which also means “to appraise” or “to estimate.” Or else, the encomium just reminded me of a habit I’d formed at pandemic’s beginning, whenever I graded my students’ short stories: sometime in the spring of 2020, I’d begun to attach a letter to each minutely annotated draft. Some of these letters ran several pages in length, others among them included appendices and footnotes. And still I never managed to convey what I wished to. Keep going, I wanted to tell them. This thing you have, don’t lose it.

About J. P. Gritton’s paintings, Jozereau and Serreau were just as effusive. In the next edition of La Grand’Goule, Serreau wrote, “All on his own, the child is searching out new means of expression.” He had, in other words, taught himself how to paint. These paintings, Jozereau went on to suggest, “demonstrate the same stunning qualities as his sketches, but their effect is much more complete.”

What’s odd is that I’ve never been able to find the paintings reproduced in La Grand’Goule, the ones Serreau and Jozereau gushed about. In fact, the goat remains the only painting of Gritton’s I’ve ever seen. From a brief biographical sketch that appears in Les Peintres de Poitou, I know that J. P. Gritton began showing his oils at the Salon d’Orientine, the region’s most prestigious art show, in 1935. But nothing appears in the annals of La Grand’Goule about these landscapes (Cour de ferme, Marine) or the one he showed the following year (Bords de la Vienne) or the pair he showed the year after that (Intérieur d’étable, Bouefs couchés). As far as I know, after publishing Serreau’s feature in the December of ’33 edition of La Grand’Goule, Jozereau went nearly four years without so much as mentioning Gritton’s name.

I can’t help wondering what the wunderkind made of this fact. I can’t help wondering if maybe, almost in spite of himself, J. P. Gritton had grown hungry for Jozereau’s praise? Or else J. P. Gritton had suspected the truth all along: that he’d only appeared in the pages of La Grand’Goule as curiosity, as folderol—almost, as freak.

In the two-page obituary of J. P. Gritton that appeared in the December of 1937 edition of La Grand’Goule, Raoul Jozereau wrote with the usual grandeur:

In the cemetery I told the devastated parents, “All of the painters of the Orientine are gathered here today. The faithful among them suppose that a picture book must’ve been needed for the little children of heaven; as for the others, that his life was, alas, like the first light of a dawn so brilliant that it will forever brighten your days.

Or else the problem with this story is that it’s hard to remember the me I was back then. In December of 2019, I couldn’t have told you who Anthony Fauci was, for example, and I understood an N95 mask to be something worn in the vicinity of paint fumes. I would’ve guessed “social distancing” to be the name of an alt-punk group from Los Angeles. Which is by way of saying, I can’t really imagine a time in which the most urgent question on my mind was How many people are going to come to my book launch?

The answer, either way, was seven. Eight, if you count me. There was an accident a few miles down the interstate from the bookstore that hosted the event. But the truth is that eight people would prove to be one of my bigger audiences. By February of 2020, just as the three-month Window of Success was sliding shut, I’d begun to recognize a certain expression on the tired faces of bookstore managers: a narrow, slightly constipated look in their eyes, not quite pitying and not quite resentful. I felt bad for them. Here they’d gone to the trouble of setting out folding chairs and amuse-bouches, opened a bottle of wine—and nobody’d come to drink it. The publicist at my press told me not to worry about such things. People would find my work by other means, she said. I wanted badly to believe her, but by then I knew better: I knew that when you typed “J.P. Gritton” into a search bar, you found no gushy reviews in the Globe, Chronicle, or Times, and that a Google image search directed you to the online archive of the Musée Ste. Croix de Poitiers: a painting of a goat signed by me, dated ninety years ago.

On January 15, 2021, about a week after Congress reconvened to count the electoral votes of the previous presidential election, four days before what would have been J. P. Gritton’s ninety-sixth birthday, I received an email from Stéphane Semelier, an archivist at the Musée Ste. Croix.

“Dear Mr. Gritton,” read the email, “it is with pleasure that I respond to your inquiry. Jean-Pierre Gritton was a young Poitevin art student who died in the summer of 1937 in Fouras, Charente-Maritime, at the age of thirteen.” Included as attachments to Stéphane’s message were a few of Gritton’s charcoals—tigers, wolves, bears, a jai-alai player—and half a dozen rave reviews. Among the reviews of his art were the features Raoul Jozereau wrote for La Grand’Goule, a brief biography from a book about the painters of Poitou, and exactly half of J. P. Gritton’s two-page obituary spread.

I don’t know exactly what I felt, wading first through Stéphane’s email and then the twenty or so pages of archival material. Curiosity, sure, and something I might’ve mistaken for excitement. But more than that, I felt a weird kind of unbelief. This nine-year-old prodigy takes Poitou’s art world by storm and then he—dies? It was somehow too simple, too neat. And yet hadn’t it been a year of premature endings? Endings in intensive care units or in waiting rooms or on the side of the road in Georgia or on a sidewalk in Minnesota or in a bed in Kentucky.

As the weeks and then the months went by, I kept on thinking about a sentence I’d read in the three-paragraph-long biography from Les Peintres de Poitou: “All the extraordinary promise this young Poitevin might have realized in the course of a normal career was cut short by his sudden disappearance, aged thirteen.” I couldn’t make sense of this line. Jozereau’s obituary had mentioned a coffin, a hearse. Was the hearse empty? Had J. P. Gritton died, or simply vanished?

Back then, it seemed an important question—maybe even an urgent one. I should explain that the town where J. P. Gritton suddenly vanished is on the Atlantic Coast, that an image search yields a series of lush seascapes: white-capped waves crashing against a stone-walled fortress, the spire of a handsome church rising over a rocky beach. Probably, in some idiot corner of my mind, I was imagining J. P. Gritton in a little rowboat, rowing forever. It would take me many weeks to realize that the phrase “brusque disparition” has none of the sexy uncertainty of “sudden disappearance,” that it’s just a euphemism—like saying “sudden passing” when you mean something else.

I wrote Stéphane on a Friday in late March—Friday evening, in Poitiers—and he wrote me back first thing Monday morning. Included in his reply, he said, was the missing second page of Jozereau’s obituary. As for my question about the precise nature of the young artist’s demise, Stéphane explained that every source on the subject spoke of a premature death without specifying the means. Which makes sense, I guess: if you’re writing an obituary for a thirteen-year-old artistic prodigy, you’re not going to waste any ink on cause of death—especially if it’s something as banal as a case of pneumonia, a burst appendix, a touch of Spanish flu. In other words, I still don’t know how J. P. Gritton vanished, but I know for certain how he did not.

In the missing second page of Gritton’s obituary, Raoul Jozereau tells his readers with morbid relish that J.P. Gritton knew he was going to die but, for his mother’s sake, “he pretended to hold out hope.” When she briefly stepped out of the room, Gritton reportedly turned to the priest who would go on to deliver his last rites: “Mais je veux mourir en scoot,” he said. That is, But I want to die in a scooter accident.

Rest in peace, Jean-Pierre Gritton. May the picture books you illustrate for the children of heaven be met with breathless praise. May your paintings hang forever on the walls of the Musée Ste. Croix. And may we be forever grateful to know neither the hour nor the manner of our sudden vanishing.

Image acknowledgments:

-

From “Et… celui de demain” by Raoul Jozereau. From La Grand’Goule: March, 1933.

-

Un bouc, © Musée de Poitiers, photograph Christian Vignaud

-

From “Et… celui de demain” by Raoul Jozereau. From La Grand’Goule: March, 1933.

-

From “Et… celui de demain” by Raoul Jozereau. From La Grand’Goule: March, 1933.

-

From “Deux peintures de Pierre Gritton” by Fernand Serreau. From La Grand’Goule: December, 1933.

-

From “Les obsèques d’un jeune artiste poitevin: Pierre Gritton” by Raoul Jozereau.

-

From La Grand’Goule: December, 1937.

***

JP Gritton’s novel Wyoming, a Kirkus best debut of 2019, is out with Tin House. His awards include a Cynthia Woods Mitchell fellowship, the Meringoff Prize in fiction, and the Donald Barthelme Prize in fiction. He is an assistant professor of creative writing in the department of English at Duke University.

SEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Blast

Apr 12 2024

“The Red Button” by Jim Steck

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. “The Red Button” takes place in Southern California in 1974, when… read more

Blast

Mar 28 2024

“The Troop Leader” by Brynne Jones

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. In Brynne Jones’s “The Troop Leader,” the adult chaperone of a… read more

Blast

Mar 15 2024

“Pete Pete’s Putt Putt Palace” by Adam Straus

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. In “Pete Pete’s Putt Putt Palace,” Adam Straus tells the story… read more